Extract from talk given at the Hong Kong Literary Festival

14 March 2007

I suppose it was inevitable that if I was to write a book, it would be in the historical fiction genre. They’re the sorts of books I love, and I was lucky, as a schoolboy, to be taught by George Shipway, who, in his day, was a very successful historical novelist, writing in the tradition of Alfred Duggan, who, to my mind, was the master. Sadly both of them are more or less out of print now. But I remember Colonel Shipway fondly. One wintry day back in 1965, abandoning a geography lesson, he told us the tale of the Roman General Suetonius Paulinus, the man who defeated Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni. Colonel Shipway described the battle. It was spell-binding. He drew on his own experience as a cavalry officer on the Indian Northwest Frontier to describe what it must have been like for the Romans in Ancient Britain. What we didn’t realise was that he was writing a novel on the subject. One day he turned up in London with a manuscript of what eventually became the bestseller, Imperial Governor. “We love the book,” his nervous publishers told him. “It’s a wonderful historical reconstruction…But, Colonel, these are the sixties and nowadays readers want a bit of – um – sex.” “Sex?” he thundered, twiddling his monocle and bow tie, his moustaches bristling. “This is a book about soldiers, sir!” “Yes, Colonel,” they stuttered, “but…readers’ tastes today…” He went away fuming. The next few days he was a terror in the classroom, and we would watch him pacing over the games pitches with his two Scottish terriers. A fortnight later he went back to London, and in due course the book came out. My goodness, we schoolboys loved it. The scene with Suetonius Paulinus having it off with Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes on the cross trees of a racing chariot as it galloped at full speed over the Pennines was as explicit as it was daring. Colonel Shipway never looked back. The sex scenes in his Agamemnon were – well, not what you would show your grandmother! I mention this because I had a similar experience when writing my own first novel. I had put some sex scenes in it – but my editors wanted more. And that’s another lesson about historical novels. To be commercial they need to suit the mores of your own times! So much for historical authenticity!

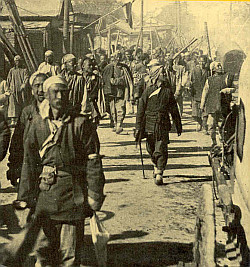

The idea for my first novel, The Palace of Heavenly Pleasure, came to me one day as I was walking along the Great Wall outside Beijing. It was a hot day and as you can see I am rather fat, and my companions were far ahead of me, and to take my mind off the never-ending ramps of crumbling steps, I thought of a conversation that I had had with the journalist and novelist, Humphrey Hawksley, the night before. We had been watching a tele-drama of Conrad’s Nostromo and had rather drunkenly decided that what gave a novel power and drama was moral choice. As I climbed the steps, a vivid picture formed in my mind: Two men were escaping something terrible. It was night, and they were on one of those railway hand-pull carts. They hated each other, representing two opposite moral poles. The one was an idealist, the other a pragmatist – but in order to survive they had to work together. As I pondered this strange image, my mind turned to the Boxer Rebellion. My own great grandfather had been a medical missionary in Manchuria in 1900 and narrowly escaped with his life; the Boxers came in by the South gate of the city as he went out by the North. My grandmother used to tell me these tales when I was a child and it fired my imagination. Over the years I had read much about the period. Yes, I thought. The Boxer Rebellion would be a perfect setting for a moral struggle between good and evil, idealism and pragmatism. I could base one of the characters on my own great grandfather. I could make him a good, idealistic Christian and have as his foil a worldly-wise Chinese Mandarin, who himself is not a bad man, but whose every action is governed by the dictates of expediency. This was a subject, after living and working for more than fifteen years in China that was close to my heart. After all, in every business negotiation in which I had participated all these years, there had been a culture clash, when the Western way of doing things by its arcane rules came up against sheer Chinese pragmatism. The novel, which was forming in my mind, could be about this clash of cultures.

The idea for my first novel, The Palace of Heavenly Pleasure, came to me one day as I was walking along the Great Wall outside Beijing. It was a hot day and as you can see I am rather fat, and my companions were far ahead of me, and to take my mind off the never-ending ramps of crumbling steps, I thought of a conversation that I had had with the journalist and novelist, Humphrey Hawksley, the night before. We had been watching a tele-drama of Conrad’s Nostromo and had rather drunkenly decided that what gave a novel power and drama was moral choice. As I climbed the steps, a vivid picture formed in my mind: Two men were escaping something terrible. It was night, and they were on one of those railway hand-pull carts. They hated each other, representing two opposite moral poles. The one was an idealist, the other a pragmatist – but in order to survive they had to work together. As I pondered this strange image, my mind turned to the Boxer Rebellion. My own great grandfather had been a medical missionary in Manchuria in 1900 and narrowly escaped with his life; the Boxers came in by the South gate of the city as he went out by the North. My grandmother used to tell me these tales when I was a child and it fired my imagination. Over the years I had read much about the period. Yes, I thought. The Boxer Rebellion would be a perfect setting for a moral struggle between good and evil, idealism and pragmatism. I could base one of the characters on my own great grandfather. I could make him a good, idealistic Christian and have as his foil a worldly-wise Chinese Mandarin, who himself is not a bad man, but whose every action is governed by the dictates of expediency. This was a subject, after living and working for more than fifteen years in China that was close to my heart. After all, in every business negotiation in which I had participated all these years, there had been a culture clash, when the Western way of doing things by its arcane rules came up against sheer Chinese pragmatism. The novel, which was forming in my mind, could be about this clash of cultures.

The period of the Boxer Rebellion itself was a perfect backdrop. It was a time of great confusion, change and moral ambiguity. The western powers were bringing modernity with one hand, but snatching territory with the other. A feudal Chinese court was struggling to survive in a new age. The actions of the Boxers themselves were ambiguous – simple peasants enticed by superstition, coerced by a corrupt court into an anti western movement that was doomed from the beginning. Who was using whom? What games inside games were being played by the powers that be, the mandarins, the criminal elements of the secret societies? As I wandered the Wall – my friends were long out of sight – I recalled a poignant eyewitness account from one of the books I had read, when the Governor of Taiyuanfu, Yu Hsien, beheaded 70 foreign missionaries, their wives and children:

“….When the women were taken, Mrs Farthing had hold of the hands of her children who clung to her, but the soldiers parted them, and with one blow beheaded their mother…Mrs Lovitt was wearing her spectacles and held the hand of her little boy even as she was killed….” And so on.

As it happened a friend of mine had sent me unpublished letters written by one of the victims, his great uncle, in the two weeks before this massacre happened. They were agonizing to read, moving from confidence that the authorities would rescue them, to a realization that the authorities were behind this, to an acceptance of certain death, ending on a note of Christian fortitude:

“Somehow I know that the Lord will treat us mercifully. And I have no doubt, my dear James, that sooner or later you and I will be reunited, and we will walk the heather once more. (Can there be Heaven without heather?)”

I knew I had the dramatic central scene of my novel. But I thought further, what if I gave my Christian doctor the chance to be rescued at the last minute? It would mean he would have to compromise all his principles, leaving his flock to die, in order to save his own wife and children. Here was the moral dilemma I was seeking. A conflict between expediency and duty, right and wrong. I had the seeds of my novel.

I won’t tell you how, when I reached the end of the Wall, I found all my friends were long gone, and how I had to hitch a ride on a handcart five miles to take me to a village where I could find a taxi for the three hour drive to Beijing, and how my friends were so worried about my disappearance that they called the police to scour the hills … that would be embarrassing.

But I wanted to tell you the genesis of this book, since it rather backs up the theme of this talk. It was the story that was important to me all along, rather than a desire to retell a historical episode. The history at the end of the day was background. Atmospheric and interesting enough, I hope, but background. Of course I tried to make the actual history as accurate as I could. But I set the scene in a fictitious Chinese city, and peopled it with characters I invented – Mandarins, missionaries, adventurers, soldiers, brothel keepers, bandits and muleteers. That gave me the freedom to tell the tale I wanted to tell, to develop my themes, and hopefully to be entertaining in the process.

Before I finish I’d like to tell you one last story. I was listening to Frank McClynn – a good popular historian – on the radio on my last trip to UK. He was describing the great Norse hero, Harold Hardrada, whose whole life reads like a novel. Born in Norway, he became a soldier of fortune. In his time he was a member of the Varangian Guard in Byzantium and blinded an Emperor, accompanied the Empress Helena to Jerusalem to find the True Cross, married the daughter of the King of Rus in Kiev, and fought marvellous wars from Sicily to Trondheim. Ultimately he was defeated and killed by Harold Godwin at the Battle of Stamford Bridge which got him into “1066 And All That” (a most authoritative tome) and Common Entrance History examinations for generations of little English boys like me. The interesting thing McClyn was telling us, however, was that Harold was also a poet, and the subject matter was himself. Apparently, even as he was wielding an axe at Stamford Bridge, seeing his army die around him, he had behind him a scribe – and as he was fighting what he knew was his last battle he was composing verses about his own death, because he wanted to get the record straight. Lopping off heads, he composed a stanza, and then had the scribe repeat it back to him. He thought it infelicitous and composed another (this as he was plucking arrows from his pectorals). Now THERE is a dedicated historical novelist! (We had to wait until Hemingway before we found another nutter who plotted his own life as a historical novel) – but there is a serious, serious point here. Why was he doing it? Quite simply, Harold wanted to ensure his immortality. He wanted to make sure a STORY was left behind him. A MEMORY. For only in stories repeated by generations after would there be any indication that he ever existed. (Beowulf was all about that before the Christian scribes got to the poem). And Harold had a point. History IS memory through the medium of a story, a poem. It is the hero’s only path to eternity, and a light for future generations. The wonderful truth is that the lives of men are their own fictions that are immortalised in the memory of the tribe. And THAT’s why we read history and why we read historical novels. The story is all.