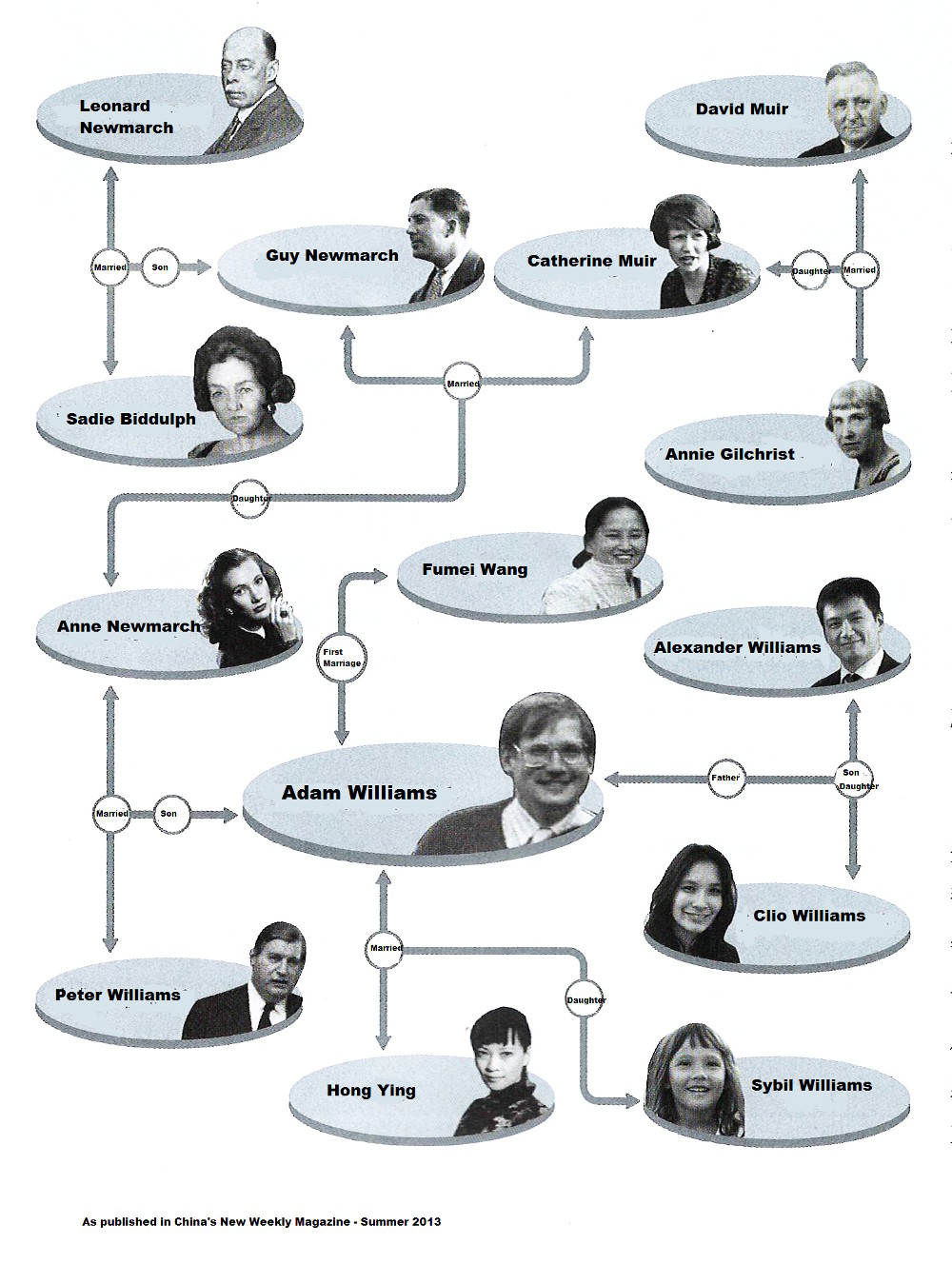

Article written in 2003 for Adam’s family archives

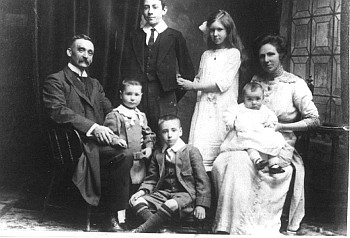

This picture, taken in about 1913, shows a medical missionary and his family on leave from China. The moustached paterfamilias on the left is Dr David Muir, from the Scottish Missionary Society, Edinburgh, who since the 1890s had practiced medicine in Northeast China (or Manchuria as it was then called). When this photo was taken he had recently become the joint director of the surgical unit of the new Mukden (Shenyang) University Hospital. Two years before that he had received a medal – a large golden dragon – from the Ch’ing Emperor for his work in walled cities inflicted with cholera and plague. He had had an adventurous life in China. In 1900 he, his wife and his eldest son, Bertram (the self-possessed youth at the back of the photo) had to flee by the north gate of the city of Changchun to escape the Boxers coming in through the south gate. In 1905 he had been the only doctor on the Port Arthur front of the Russo-Japanese War; he treated both armies, smuggling himself between the lines at the bottom of a dung cart; if he had been caught in the middle by either side he would have been shot as a spy. He was undoubtedly a brave man. Indeed he had much to be proud of, which perhaps explains his smug expression in the photo, but he also had a twinkle in his eye: he was a humorous man with a love of adventure fiction, especially cowboy stories, and was much loved by his large family.

Dr Muir was the model for the central character of my Boxer novel, Dr Edward Airton, who is also a medical missionary in Manchuria, and with many of the same attributes: Airton like Muir has a sense of humour, not a little bravery, and a taste for cowboy fiction. Dr Muir’s wife, Annie – severe but fine featured in the photograph – is the model for Dr Airton’s formidable wife, Nellie. By all family accounts Mrs Muir was quite as tough as the fictional Nellie. She survived her husband by several years, dying just after the Blitz in London in the mid forties.

Dr and Mrs Muir were my maternal great grandparents. My maternal grandmother, Catherine, was the young girl who stands in the back row of the photo.

Catherine, born in 1903, three years after the Boxer Rebellion, spent her very early years in China but at the age of about ten her parents took her via the Trans Siberian Railway to Scotland where she was to spend the next eight years at various boarding schools. Aged eighteen, just after the First World War had ended, she came out to China on a P&O liner and arrived in the northern city of Tientsin.

By then her father had stopped his missionary practise and had become senior medical officer to the Kailan Mining Company, headquartered in Tientsin. Her brothers, Bertram – nicknamed Ching – Edward (on his father’s knees in the photo) and David (the babe on his mother’s knees) worked with their father. They all went on to distinguished medical careers: Ching founded several hospitals in Tasmania and South Australia, Edward became the Queen’s Surgeon and operated (unsuccessfully) on the King of Greece, as well as (successfully) on the Queen Mother, and David was for many years a senior doctor in Shell. The other son, Stephen (sitting centre) did not become a doctor but also worked for the Kailan Mines. He had an active war; was one of Windgate’s Chindits; became an intelligence officer and afterwards was in charge of security for various nuclear power sites round Britain.

But this was all in the future. When Catherine came out to China in 1920 it was to join a large established family, almost a dynasty, of doctors. Shortly after her arrival she married into another expatriate dynasty in North China, this time of railwaymen.

Leonard Newmarch had come out to China, also in the late nineties, to build China’s first railway, which stretched from Peking to Mukden (Shenyang). It opened just before 1900 but Leonard saw opportunities in China and stayed on. He came from a wealthy timber trading family in Beverley, Yorkshire. Although Leonard was an engineer, he considered himself rather grand, and his wife, daughter of an Anglo-Irish landowner, also had airs. Their son, Guy, grew up in a wealthy household. He was devastatingly handsome, and fashionably affected; he always dressed impeccably, keeping a handkerchief in his sleeve. He also became an engineer, designing many of the railway bridges in Manchuria. In 1920 he married red haired Katie Muir. It was a grand wedding for Tientsin, and was much talked about, probably because the couple were so handsome. It was an unhappy marriage, however. After a few years, Catherine began to seek solace in the high life and affairs with naval officers; Guy, disinterested, perfected his stereo system, the first to be introduced into China, and shot duck in the marshes near Taku, traveling there and back in his private railway carriage. Their daughter Anne, my mother, grew up in a large house, with ten or more servants, with every luxury and indulgence imaginable lavished upon her, but it was by parents who did not talk to each other. Unhappiness was never far away when it came to the Newmarchs.

I suppose that the character Manners in the novel owes something to this family line. He, like the grand Newmarchs, also came from Beverley, and like Leonard Newmarch, he gets a job on the Peking-Mukden railway. He has some engineering skills – that is as far as the obvious similarities go. But there is that hint of the parvenu, the cad, in his character; I think that Leonard’s generation of the Newmarchs were very much on the make, and Guy’s preciousness was perhaps a reaction, a result.

It all ended badly. Come the second world war, Catherine and her daughter, Anne, my mother, took a Japanese ship back to Britain. They sailed as neutrals through the submarine infested seas with all lights blazing, and arrived in England on the same day that on the other side of the Channel British troops were being taken off the Dunkirk beaches (those rescued included three of Catherine’s brothers in the photo above). Guy Newmarch had meanwhile stayed in China to pack up his collection of snuff boxes and deposit them with the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in Tientsin. This task carefully done, he decided in a leisurely fashion to travel south. He had reached Hong Kong when the Japanese invaded. Guy spent four years in the concentration camp in Stanley. It broke him. At the end of the war when the emaciated remnant of this once elegant man had returned to London, he used what he could remember of his engineering skills to try and build a paddy field in Holland Park. My grandmother promptly divorced him and he disappeared off to South Africa. My family never really heard from him again.

Their daughter, Anne, an art student and then a model with Hardy Amies, had meanwhile married, in 1947, a penniless young artillery captain from Epsom called Peter Williams. He talked rather pompously about India where he had served in the war, and borrowed a great deal of money to invest in a marmalade business which went bust. So Anne used her Far East contacts, and got Peter a job with an old China trading house called Dodwells, which sent him to Japan and later Hong Kong.

And that was where I was born, in 1953. My first memories are of donkeys and palm trees on Repulse Bay, and a white tunic-ed amah pushing my pram by a tree in which a snake squirmed. Hong Kong in the fifties and sixties was still an old fashioned colony. Only in the seventies did it begin to become the Asian Manhattan which it is today. What I recall from my childhood are pigtailed women in cheongsams, junkies and beggars by the ferry, markets where Chinese opera jangled and where one was intoxicated by the rich scent of Asia, fleets of sailing junks moving leisurely between the islands, and servants wherever one turned. (In my book I have borrowed the names of the cook and housemaid who served my parents. Ah Li and Ah Sun had an affection and love for my brother and me which was as fierce and protective as a wolf for its cubs; I honour them).

Hong Kong was not China. It was British. Of course. But China loomed over the hills, an ever present menace. And in my house it was always there. My mother taught me the same nursery rhymes that she had learned as a child in Tientsin. These had been taught her by her Manchu amah, daughter of a Bannerman, who had looked after her since she was an infant. And when I was naughty I was scared into good behaviour by threats that the various Twenties warlords who had scared my mother in her childhood would come and get me.

My mother told me many stories about growing up in the China between the war years. My grandmother, Catherine, told me more – about her parents and their adventures with the Boxers, about life in the North of China during the civil wars – when their train once steamed through a battle, and when she once had to be evacuated onto a British gunboat. My godmother – my mother’s best friend from her Tientsin childhood – would tell me stories too; I remember how scared I was when she told me how she had walked along the beach near Pei Tai Ho, and there on the strand she had seen the cut-off heads and the dead trunks of twenty pirateswho had just been executed…..China was ever present in my life and it always had a resonance and a romance, as well as being – if I were being truly honest with myself – a little scary,.

I ended up living in China. My father from his uninspiring beginnings in marmalade had gone on to become one of Hong Kong’s most successful businessmen. He was Chairman of this company and that one, and, as Chairman of the Jockey Club, JP, and Member of the Legislative Council, he dispensed a great deal of patronage. He was a big, cigar smoking man, a taipan, rather larger than life, and he lived in a big house on the Peak.

Inevitably I moved into this world. Abandoning an English winter where I was unsuccessfully trying to sell encyclopaedias I took the offer I couldn’t refuse and flew home to Hong Kong on the excuse that I would do something useful like learn Chinese. I did so. I studied in Taiwan where I married – Fumei became the first full blooded Chinese in our family in four generations in China. By way of a trade promotion body in London, I got a job with Marconi in Peking and then the old China trading company, Jardine Matheson, in Shanghai. I have lived eighteen years in China working for this old “hong” and now I have my own experiences of China, including the 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square where I was present. I probably know as much about China as any of my forebears.

But for romance – the romance of China – I still tend to look back to the past, and my family history. Neither missionaries nor railway engineers are quite on the “right” side of history nowadays; they both very much represent the imperialist oppressor in the eyes of both the Chinese communist and the politically correct British liberal. What were they doing there in the first place? Their meddling brought the Boxer Rebellion down on their own heads! No doubt that it is all true, but they lived in colourful times to different mores from our own, and it is fun thinking back to how they might have thought and behaved.

Adam Williams’ Family in China 1893 – 2013