Letter found by Peter Newmarch in his family vault, Greytown, Kwa Zulu, South Africa – February 2010

Introduction

I recently posted an article on this website about my family connections with South Africa (A Boyhood Among Zulus) and I mentioned that my distant South African cousins (who arrived there in the late 1840s) had discovered a vault full of photographs and letters dating back to the Nineteenth Century. Since I wrote, another great trunk of letters has been found This is a remarkable cache. Once Mike Newmarch and his son, Peter, have catalogued the whole trove, they will have a unique picture of a South African settler dynasty – with invaluable references also to their many relatives either left behind in England or scattered in other parts of the Empire, like my branch of the Newmarch family, that made its home in China.

Peter Newmarch has just transcribed one of the first of the letters. It is written by my great, great grandmother, Julia Newmarch, wife of a timber merchant in Yorkshire, to her cousin by marriage, Margaret Mary Newmarch, a second generation settler in Greytown, Natal Colony, South Africa. The year is 1899.

It is an ordinary enough letter. Julia commiserates Mary on the death of her father. She describes the illness of her own husband, John, over the winter of 1898. She thanks Mary and her family for helping Julia’s son, Harry, who has just emigrated to South Africa. She passes on news of her other son in China, then gossips about relatives scattered around the world. What she writes would have been considered unremarkable in those high Imperial days. Her letter would have joined bundles of others, sacked into the holds of Union & Castle, Blue Funnel or P&O steamships to be delivered weeks or months later to relatives at the other end of Empire.

For us, however, in the early 21st Century, those humdrum letters open a window into a forgotten world.

I have had enormous pleasure over these last three weeks, listening, every day, to a BBC 4 radio programme called “A History of the World in 100 Objects”. I strongly recommend it. Every day, the Curator of the British Museum takes an object, dating back sometimes thousands of years – it could be a stone axe, a carving on a mammoth’s tusk, or a piece of Egyptian papyrus. He describes it, he invites experts to comment and in 14 minutes reveals to the listener what can be learned from it, in so doing filling in like pastel colours aeons of history. A dead object brings the past to life.

For me, my great, great grandmother Julia’s letter does the same. Of course there is particular personal resonance. She is providing living details of family members who were otherwise just anonymous names on family trees but who now have a real, almost physical, relationship to me. Their ghosts have been conjured and can never go back to the grave of oblivion again.

But the letter is more than a family heirloom. It is a historical document embedded in its time, emblematic of its day, and even for a stranger it will speak of a world of the past that has been shared among many families. It is nothing less than a snapshot of Empire.

1899 – two years after Queen Victoria’s Jubilee. The Newmarches of Hessle are comfortable on the upper rungs of their society. They are ship and timber merchants, confident members of the industrial and mercantile power house that has spread globalisation and the gold standard over the planet. Julia is describing a disturbing illness that has overcome her husband – he is in his late sixties, he has been working too hard – but he has the best care that money can buy – a live-in nurse, daily visits from the local doctor, twice weekly visits from the medical specialists in Hull and in between a veritable parade through the health spas of England – Bournemouth, Leamington, Bath. As she writes the letter – one can imagine her, dressed in high-necked, frill collared velvet, sitting at an escritoire with her lorgnettes and feather pen poised over the blotter – her husband lowers his newspaper from his comfortable armchair by a roaring fire. Is he in a dressing gown with a tasselled tarbush on his head? He is still after all convalescent. Perhaps he coughs a little as he murmurs in a considered tone, “Mind to send my love.” One can see the scene. It could be a painting by Frith. John may be ill. They are mourning a death. No doubt Julia has been beside herself with worry – but her paragraphs are ordered and stately. Underlying all there is calm and decorum and, understated, power – for this is the great British Middle Class looking out at their Empire.

In which they have invested time, money and the blood of their kin. Nobody says there has been no sacrifice. In 1849, three of John’s cousins, sons of his father’s brother, William, God-fearing men, gentlemen all – this was no poor family (John’s father after all was Vicar of Hessle and Chaplain to the Earl of Stafford) – in a pledge of adventure and ambition, risked all on a passage to Durban in the still virginal Natal Colony, South Africa. For the family left behind they might have been setting off to the end of the world.

And when they arrived, it must have seemed so. Their promised land was an endless sandy beach, a desert.. It must have taken courage to step on into the hinterland, strong in the faith that this unprepossessing continent would make them their fortunes – if they survived the hardship.

One didn’t: young Thomas was killed by a rhinoceros in Zululand. Another, John, had a larger ambition and wanderlust. He saw Africa only as a staging post. His mercantile star took him to Fiji and Australia. That, for those at Home, really WAS the end of the world, and he wasn’t the only member of the family to go so far afield. Members of the older generation were also sensing opportunity and riches in Victoria’s new Empire. Rainbows were stretching out to the furthest reaches of the earth and there was a pot of gold at the end of every one of them – morally sanctioned too. It was a noble purpose to spread civilisation and Christianity. Julia’s husband, John’s own brother, Henry, suddenly heard the siren’s call and set off for New Zealand. What before 1850 had been an insular Yorkshire family that hardly strayed beyond a circle of Whitby, Hull and Sheffield, was suddenly scattered across the world. Every step of each person’s journey was the result of an individual decision based on unique circumstances, but they joined others who had gone before and after them. An Imperial breeze was blowing them all.

It grew stronger as Britain’s power and wealth expanded: in 1869 a fourth brother, Edward, gave up his work on the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincoln Railway and followed his siblings to Africa. He threw himself into the community in Greytown – the town where George William had already settled. Until his early death in 1884 he was Deputy Sheriff, Hon. Treasurer to the Agricultural Society, President of the Literary Institute, and Worshipful Master of the Umvoti Masonic Lodge. The institutional trappings of England had followed in the settlers’ wake, making their new found prosperity respectable and reinforcing links with Home. Pax Britannica was spreading and the Newmarches were part of it. Edward and George William became landowners, squires of all they could see around them, in the rolling hills of what had once been Zululand and which was now rich farm and pasture land. George William had done more. He had married a Scottish settler’s daughter in Pietermaritzburg and fathered a dynasty of fine sons – steady men as he had been, abstemious, careful, never forgetting their heritage and their cousins at Home. They were also a hardy breed – George William’s children grew up learning Zulu; they were hunters as well as farmers, crack shots like the Boers, and knew their way round the country they had settled in as well as the Natives they had displaced.

It was the women who kept the continuity. In every generation there are keepers of the family records, maintainers of those invisible links with those who have gone overseas, celebrating births, mourning deaths, extending the ever growing tapestry. This letter of Julia’s was part of that process. Every paragraph is like the weave and thrust of a shuttle, passing on threads of information in one direction, asking for news in the other. Tikkie Mary, George William’s daughter, who lived in a cottage named Hessle after the village in Yorkshire from which the Newmarch brothers had emigrated, was Julia’s counterpart in Africa. A spinster, she looked after the old and was the post box for the rest of the family – at home and abroad. Every family had somebody like her. It was her job to keep track of everybody’s lives.

What is extraordinary about Julia’s letter is that in six brief pages it traverses the generations. Her own generation, those born in the 1830s, are in their sixties now and life is taking its toll. The death of Cousin George in Africa is a shock. He was a rock, a survivor, the patriarch who had founded a settler dynasty – and he had gone so suddenly and unexpectedly. Julia’s own certainties are being challenged closer to home. Her own husband, another man of energy who all his life had overseen a large trading business, has been laid down over the winter with an alarming skin disease with complications that involves an army of doctors and a tour of the health spas to get him right. It has clearly been stressful for her and worried her – in a letter of condolence she spends more time talking about John’s illness than Cousin George’s death – but at the same time she is aware that age comes to all, people reach their time early or late. Perhaps it is a source of comfort to her that her husband’s Aunt Emily, his father’s sister, is still looking after a great aunt from an even older generation, who is 98 years old: “She knitted my husband a comforter and sent it last week for him to wear here. Dear old thing, it’s truly wonderful.”

It is also important, in the light of a death in the extended family, to make sure of the health of other older members of their scattered clan – her husband’s elder brother, Henry, for example, who made his life in New Zealand. There are several ulterior motives in Julia’s decision to write to Mary, because she knows she is a channel by which she can contact others who can help her. Mary has an Uncle in the same part of the world as Henry – John, the brother who left Africa for Fiji and who is now living in Australia. In a letter to George William before his death she had suggested that this John, just over the water in Sydney, should get in touch with Henry. As it happens we know he did so, because another letter that Peter Newmarch has discovered is John’s report to Tickie Mary: he is disappointed, Cousin Henry only sent a photograph – but Julia does not know this, she is still pressing action from her side of the world on a branch of her family on the other.

But more important than all is the new generation, and here Julia also is looking for favours (this is how an extended family should operate, after all; that’s what ‘s having a large family is all about)). For the Imperial siren is still calling and two of her own sons have answered its call and gone overseas. One, my great grandfather, Leonard, is in China. He is doing well working for the North China Railways and Julia boasts “He is [Chief Engineer] Mr Kinder’s right hand man.” (He wasn’t, he was a lowly assistant engineer – but mothers are proud the world over!). She also boasts about Leonard’s two-year-old son, my grandfather, Guy – “so intelligent”. Daughter-in-law Sadie, a South African girl Leonard met when he worked on the Cape Railway, had not been quite blue blooded enough for the Yorkshire Newmarches when Leonard married her, but now she has produced a son and heir, she is “good and sweet-looking”. Forgiven and part of the family.

Of more concern to Julia, though, is her younger son, Henry Bernard Newmarch, Harry, who, the year before, had left his job in the family firm because he had not been allowed to marry his first cousin and had done the romantic Victorian thing and emigrated to the colonies. Now he was in Africa. Here business comes into the equation again. Mother and father in Yorkshire are determined he succeeds in his self-imposed exile (they have used all their contacts to find him a job) but they want also their cousins in Natal to look after him if all falls through – so there is much complimenting Mary’s brother, George, who is the closest thing to a minder for their wayward son. Julia is calling on the extended family to make sure her son comes to no harm.

And the letter inevitably ends on a note about what’s really important: property – because for that generation, wherever they were in the world, possession was the only security. She asks tactfully, but the question is pertinent for all that: after George William’s death, who gets the family farm? And then she fills the South African family in on the latest family dispute over a will.

In fact this is what almost every letter was for the Newmarches and Forsytes of that high Victorian age: keeping in touch by its very nature was talking about money.

For the reader of today, however, one sees only poignancy, for this is a ‘Golden Age’ letter. The comfortable world of Empire is already showing cracks. Within the year, Julia’s son, Harry, will find himself in a war zone; the Second Anglo-Boer War will have broken out and Greytown will be on the front line. Two of Mary’s brothers will be in the Umvoti Mounted Rifles, the local volunteer militia, on active service at Ladysmith and elsewhere. It seems highly unlikely that a young man like Harry escaped involvement.

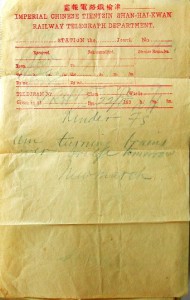

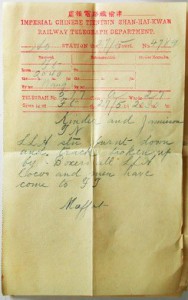

A year later, in China, the Boxer Rebellion erupts and it’s Leo’s turn to be in the thick of it: we have a telegram he sends to his headquarters in Tientsin on 22 May 1900 from his railway post just south of Shanhaiguan: “Kinder F.S., Am turning trains over bridge tomorrow” and five days later another telegram shows him in full retreat: “Kinder and Jamieson, T[ientsi]N, L[iu] L[i] H[o] St[ation] burnt down and track broken up by Boxers. All L[eonard] J[ohn] N[ewmarch]’s locos and men have come to F[eng]T[ai], Moffat”.

Telegrams courtesy of Peter A Crush and the Claude Kinder China Railways Collection

In the curt messages one can sense the fear and the danger.

Meanwhile Sadie, Leo’s wife, heavily pregnant, has been evacuated to Japan with four-year-old Guy. It is there, separated from her husband that she gives birth to Leo’s second son, Jack Moorhead Newmarch, who is in effect born the child of a refugee. In this letter Julia writes to Mary telling her how Leonard, Sadie and Guy are expected to return in 1900. It didn’t happen. History got in the way.

And within fifteen years, the comfortable certainty of the Newmarches world – Julia’s world – will have crumbled forever, with the onset of the First World War.

The Letter

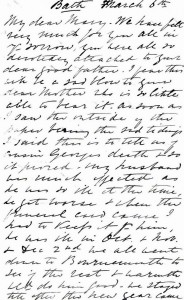

Bath, March 6 1

My dear Mary. 2

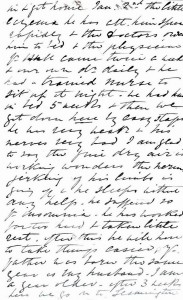

We have felt very much for you all in your sorrow, you were all so devotedly attached to your dear good father.3 I fear this will be a sad blow to your dear Mother4 who is so little able to bear it. As soon as I saw the outside of the paper bearing the sad tidings5 I said, this is to tell us of Cousin George’s death, and so it proved. My husband6 was much affected as he was so ill at the time, he got worse and when the funeral card came I had to keep it from him, he was ill in October and November and December 2nd we all went down to Bournemouth7 to see if the heat and warmth will do him good – he stayed till after this new year came in and got home Jan 2nd – the little eczema he has attacked him, spread rapidly and the doctors ordered him to bed and the physician from Hull came twice a week and our own doctor daily and he had a trained nurse to sit up at night. He had been in bed five weeks and then we got down here by easy steps, he was very weak and his nerves very bad. I am glad to say the fine dry air is working wonders, the nervous jerking of his limbs is going off and he sleeps without any help. He suffered so from insomnia. He has worked far too hard8 and taken little rest. After this he will have to take things easier. Your father was born the same year as my husband. I am a year older – after three weeks here we go on to Leamington as constant change is recommended. My oldest girl July9 is with us, she was in the south so joined us, as Ethey10 – the youngest helped to nurse so wanted rest. We left her at home with a friend.

We hear this week from our Harry11 , he has met your brother George12 at Johannesburg, he was sick of mines and leaving and going down to Durban so our Harry was to follow him March 1st. Harry has not found anything to do yet only temporary work which is over. I wonder how far Greytown is from Durban. H. expects to get work in the firm of Neame’s timber people but he had to wait.13 They said if he gets in, it will be well as he understands the business and will be well paid – probably sent to a branch at Delagoa Bay or Durban – I hope not the former as it’s unhealthy is it not? Thank you very much for all your information, altogether what I asked – We wrote to George14, H. likes him, he says he neither smokes nor takes anything to drink which H. appreciates, he is very abstemious himself – in thanks [?] he’s att. [attained? – this passage is a bit obscure] 35!15

I wonder if you’ve heard from Emily N.16 She is in Lincoln now looking after their old aunt Joan Keyworth17, age 98. She knitted my husband a comforter and sent it last week for him to wear here, dear old thing it’s truly wonderful.

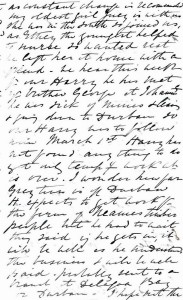

I have very good accounts from China – my boy Leo18 is Mr Kinder’s 19 right hand and is now an execution engineer and they live in a big house20. They moved while Sadie21 and her sweet boy22 were in England. Last summer she and baby and an arma23 came to us in May for three months. The baby is two years old and the sweetest child I ever saw and so intelligent. His grandfather and I and all are devoted to him and their good sweet looking young mother. Leo and wife and baby hope to come in 1900 24 as Leo will have then been in China 7 years I think – but it will only be for a few months and then a fearful parting for us.

When you write tell me who has your farm now25. I expect some of your brothers. I remember the house at Greytown of your Uncle Edward’s.26 He used to have a photo. But I expect your dear father made some alterations before he left you.

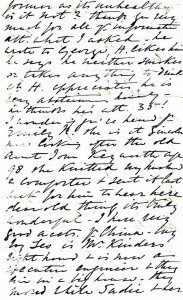

I wonder if John Newmarch27 ever went over to New Zealand to see Henry N. He talked of it – we often hear from Henry. He seems very happy and comfortable, he did not wish his poor sisters to return the money which was his due once – but Mary Anne Mrs Birtwhistle returned hers and the interest, her husband wished it and of course my husband did too but no interest – he did not think that right.

I hope Fanny28 keeps well and her two little ones – also all other members of your large family. Give our kind love and sympathy to your poor mother and accept love yourself.

From your affectionate cousin, Julia N. 29

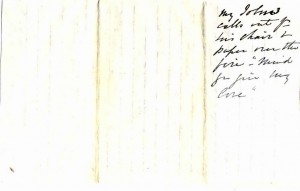

P.S. My John calls from his chair and paper over the fire – “Mind to give my love”

(My thanks to Mike Newmarch, Peter Newmarch, Belinda Pascal, Jane Wynne, Philip Coetzee, Anton Moolman and Peter Crush)

Footnotes

1 Letter is undated bar the month but the year in which this was written must have been 1899. We know from Peter Newmarch in South Africa that his great great grandfather, George William Newmarch (Julia’s‘ Cousin George’ ) died in 1898. As this letter states, the Newmarches in England heard the news in October or November of that year. This belated letter of condolence (delayed because its author, Julia Newmarch, was occupied with her own husband’s illness over the winter) is written the following March. Note: the letter is written from Bath, then, as in Jane Austen’s times, a health spa.

2Addressee is Margaret Mary Newmarch (Tikkie Mary – 1862 – 1938), Julia Newmarch’s first cousin by marriage ( her father-in-law, Vicar Henry of Hessle was brother to Mary’s grandfather, William. She lived in Greytown at ‘Hessle Cottage’(named after the village in Yorkshire from which the family originated, now an old age home, ‘Arcadia’ )

3 George William Newmarch (1832-1898), Margaret Mary Newmarch’s father. With two brothers, John and Thomas (fourth brother, Edward, a railway clerk, came later in 1869) he had left England in 1849 for Durban. Peter writes: “He came with immigrants who had to wade ashore at the Point, Durban. The road to the town was a tortuous sand track through thick bush and the streets of Durban were also sand.” Thomas died shortly after, killed by a rhinoceros in Zululand, Edward never married and John emigrated to Fiji and later Australia, but George William went on to prosper and found a dynasty. In the years before his death he had been living on the family farm, Whitcliffe, in Greytown, Natal Colony, which, it seems (from evidence later in the letter) had been passed to him by his brother, Edward, who died, aged 50, in 1884 (The Natal Times described him as a most popular and active man in the Greytown community).

4 George William’s widow, Christina Duff Doig, born Perthshire 1839 died Greytown 1913. Her family had emigrated to South Africa and she married George William in Pietermaritzburg, where she grew up. Natal was British dominated but there were many Boers who lived side by side with the English settlers. Peter Newmarch has an account of how during Christina’s girlhood she held General Botha, the Boer commando leader who captured Winston Churchill, in her arms two hours after he was born. Christina, who was best friends with Botha’s mother, had ridden on horseback over to their house as soon as she heard the news. “Makes one wonder on who’s side we were?” jokes Peter, and that does point to a poignancy that underlies this letter, reading it today, for within months of this confident exchange of family news across Pax Britannica, crack lines began to appear in the British Empire. In South Africa, friendships were broken and life changed for the settlers when the Anglo Boer war broke out in October 1899. The Greytown Newmarches were affected. Peter Newmarch writes: “Some other letters [we have] deal with how stupid the Boers were in trying to hide their tracks,…. Another speaks of the desecration of a church by the Boers with the names of those responsible etc…” A year later Julia would have two sons and a nephew involved in wars overseas: her Harry (see below) in Natal, while her Leonard (also see below) and her sister Hannah’s son, Douglas Claud, were in China in the thick of the Boxer Rebellion.

5 Peter Newmarch “The letters in the old days that carried bad news, had a black edge to them – no doubt Mary sent a letter like this and from the address Julia would have immediately known of the death (as she mentioned) . I don’t know what’s better, seeing the envelope, or just having a plain envelope and reading the news. Kind of reminds me of the American war movies where you see the black car driving up the farm road to bring the news (bad news of course).”

6 My great great grandfather, John Newmarch, Vicar Henry’s son, born 1833, Barnetby, Lincs , died Portsmouth, Hants. 1907. He was a prosperous timber merchant in Yorkshire. Son of a respected vicar from Hessle ,, in 1861 he had eloped with the daughter of Whitby’s timber magnate, ‘Owd Gideon Smales, in the process making friends with Gideon’s son, Charles. Later John’s younger brother married his wife’s younger sister, Hannah. The interlinked families of Newmarch and Smales became a Yorkshire timber and shipping dynasty.

7 From residence in St Mary, Yorkshire

8 In the family timber business in Whitby and Hull, Yorks.

9 ie Julie – Julia Mary Newmarch, born 1863 in Sculcoates, Yorkshire to John and Julia

10 Ethel M. Newmarch, born 1869, Sculcoates, to John and Julia

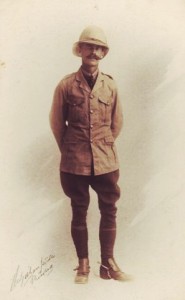

11 Henry Bernard Newmarch born June 1868 in Sculcoates to John and Julia. Belinda Pascal has a ship’s manifest which shows him coming to South Africa in 1898. (This was probably to escape England for a while because he had not been allowed to marry his first cousin, Gertrude, daughter of his mother’s brother, Charles Smales). Photo (courtesy of Belinda Pascal) shows the young man arriving in South Africa dressed for the part (or is this a military uniform after commencement of the Boer War in 1899?):

12 Probably George Benjamin Newmarch, unmarried son of George William and brother of Margaret Mary. He is two years older than Harry, so it is natural Mary (or even John and Julia), thinking the two cousins would naturally get on, suggested Harry go up to meet him in Johannesburg, perhaps to get his help to find a job in the gold mines – but . George seems to have tired of mines and decided to move to Durban.

13 Philip Coetzee has discovered a 1906 reference to a “MR. NEAME, MANAGER OF THE LINGHAM TIMBER AND TRADING COMPANY, LTD” and the presence of a Humphrey Neames in South Africa at the same period (who may or may not be the same man). His further research showed that the Lingham Trading and Timber Company of London had a variety of international businesses at this time trading timber and importing Texas cattle to South Africa on its steamships. It had a strong Portuguese East African presence. From The Key to South Africa : Delagoa Bay – 1899 (http://www.archive.org/details/keytosouthafric03jessgoog): “Beyond the Netherlands Pier — the inland side of Lourenzo Marques — stores have been run up and the whole appearance of that place altered ; further on is the fine Lingham Company Flour Mills, with a capacious granary attached, and some miles up the river the Lingham Timber Company’s yards.” Its Chairman, C H Godwin, was involved in gold mines. It is very likely the Newmarches had business contacts with the Lingham company and may even have known Neame. From this passage it is clear that Harry spent several years finding his way before he got into farming and bought the Wonderboom estate from his South African cousins. In England he was working in the family timber business (he had stated his profession as ‘timber merchant’ on the ship’s manifest the previous year) and clearly at this stage he was looking for a job in the same field and has made contact with Neame on his arrival in Durban. Presumably he got the job, making enough money to buy a cattle farm years later.

14 Belinda Pascal: “From the letter I think Mary must have given Julia and John some helpful information about contacts for Harry in South Africa and they gave Harry a helpful nudge in the right direction.”

15 This joke, if such it is, is not only illegible but also rather mysterious. Whether it’s a dig at either Harry or George, it’s odd, because neither is 35 – Harry being 30 and George 32. It might read “in thinking he’s att[ained] 35!” But, as Belinda points out, there is nothing special about 35.

16 Emily Newmarch is probably Julia’s sister-in-law, born 1840.

17 Joan could be a sister of her mother-in-law Susannah Keyworth. wife of, Henry, the Vicar of Hessle. Note: Jane Wynne has discovered that an Elizabeth Haldenby Keyworth aged 98 died in Lincoln in the June quarter of 1900, which might be the same person, only if, as Julia says, she was already 98 in March 1899 there is a slight discrepancy.

18 My great grandfather, Leonard John Newmarch, born 1867 in Hessle to John and Julia died 1953 in Cradock

19 Claude Kinder (1852-1936) who was for many years Imperial Railways of North China’s Chief Engineer and General Manager, a position that Leonard later occupied at the time of his retirement in 1928

20 This house must be in Lwanchow (present day Luanzhou just south of Shanhaiguan near the sea end of the Great Wall) where he moved to a new job in 1897. While he got used to his new job, Sadie and infant must have used the opportunity to go back to England and visit family

21 My great grandmother, Sarah Newmarch née Biddulph born Cradock, SA, 1874 died Cradock 13 Sept 1953, married Leonard John Newmarch 1894 (in Shanghai according to her death certificate).

22 My grandfather, Guy Lumley Biddulph Newmarch, born Tientsin, China, 1896, died Cradock, SA, 1964

23 sic. Should be amah ie Chinese nursemaid

24 China Railway records show that Leonard started work in China in 1893 after working three years on the Cape Government Railway (during which time he met Sadie). Julia says that in 1900 Leonard will have a long leave due to him after seven years service. In fact this was overtaken by events. The Boxer Rebellion broke out in that year. Leonard had to remain at his post on the railway line while Sadie, heavily pregnant, was evacuated to Japan where she gave birth to her second son, Jack Moorhead Newmarch

25 Whitcliffe, the Newmarch family farm in Greytown, passed on to George William’s sons after his death. Peter Newmarch says Julia most likely once saw a photo like the one below– although this was taken in about 1910.

Says Peter :“It shows a gathering getting ready for a hunt on Whitcliffe farm (commonly called just the Farm) – The man on the very left with the pipe is William John Sawden Newmarch (George William’s son) – Tikkie Mary’s eldest brother and my Great Grandfather. The little boy in the front row with “black” jersey and hat is my Grandfather (Wilfrid Leuchars). The others we have not identified as of yet. The shotgun that William John Sawden is holding is in Greytown and still as good as new and all in working order. (all engraved with intricate carvings on the metal) – I last used it many years back while still at school Dad took us to a family friends farm to hunt some ducks – they did not stand a chance. – now that I think of it, its time to fire the thing up again. – gone are the days we could just fire it off in the back yard!.”

26 George William’s brother, Mary’s uncle, Edward Sawden Newmarch

27 This refers to the South African John Newmarch, brother of George William, who also came out to Africa in 1849 and who emigrated to Fiji and later Australia. The Henry mentioned in this paragraph is Julia’s brother-in-law, her husband’s elder brother, Henry Keyworth Newmarch, born 1831, who had emigrated to New Zealand a while before and with whom, until recently, the family in South Africa had lost contact, although, as Julia says in the letter, he is in quite constant touch with his English relatives. As emerges from another letter in Peter’s possession (which also incidentally goes into detail about the circumstances of George William’s final illness) the year before Julia had written to George William telling him about his cousin in New Zealand. George William had then written to John in Australia asking him to get in touch with Henry, which he did. Julia is now pressing Mary to see if John has gone through with his plan to visit him. Now, it seems, she also wants to fill the South African family in on financial circumstances that have soured (in her view) the relationship with Henry in the past, and which mainly involved her sisters-in-law. She mentions Mary Anne (Mrs Birtwhistle), born 1833, and there are other sisters (Susan Jane, Mary, Margaret and Emily) any of whom may also have been involved.. One can only guess that some inheritance that should have gone to Henry was passed to other siblings in his absence causing family embarrassment if not a row (although Henry appears to be quite placid about the debt, it seems to nag on the others’ consciences, even to the point that they are writing to their South African cousins about it!)

28 Presumably this is Mrs Handley, née Fanny Lonsdale Newmarch, Mary’s sister.

29 Author of this letter, my great great grandmother, Julia Newmarch, née Smales born Whitby, Yorks. 1833 died 1931 in Portsmouth, Hants