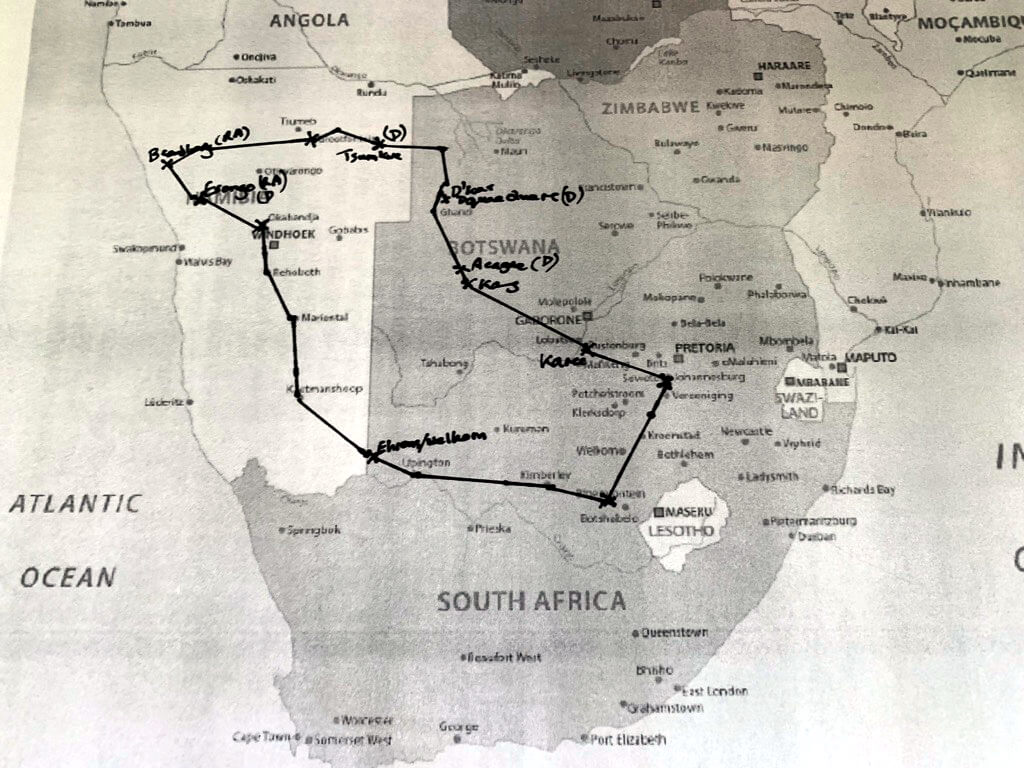

During the first two weeks of August, I drove 5,300 kilometers through three countries – South Africa, Namibia and Botswana – mostly within the Kalahari Desert, staying in Bushmen villages and visiting ancient Bushman rock art, meeting shamans and hunters, and witnessing and participating in several Bushmen traditional dances, particularly trance dances, where the shaman can sometimes go into an altered state and take on powers of healing.

My guide was Gary Trower, an archaeologist and long-term friend of the Bushmen (or San-Khoi as they are also often collectively called). Gary had lived with them for many years, and as I saw for myself in nearly every village we visited, he was welcomed as family, and with joy. Many of his friends are renowned shamans and hunters, and he himself is considered by these eminent men to be a healer in his own right. I was therefore able to benefit from access built on years of trust.

My interest was to learn about, and perhaps experience aspects that remain of a hunter-gathering society (genetically the oldest race in the world) particularly those shamanic and more spiritual elements of consciousness that differentiated early man from our own present state of being. This interest of mine has grown out of various excursions that I have taken around the world into an increasingly ancient past since 2015 (see https://www.adam-williams.net/2018/11/27/paleolithic-pilgrimage-france-october-2018/ ).

I had read that much of the old Bushman culture has disappeared. That over the past decades the Bushmen’s free life on the veldt has been restricted to reservations and the old ways have become more and more difficult to pursue. The modern world has been pulling them into a new future as much as it has been repressing their traditions. Their customs have been repackaged for tourists. It provides income, where otherwise there would be none.

I wanted to see what if anything remained of the Old.

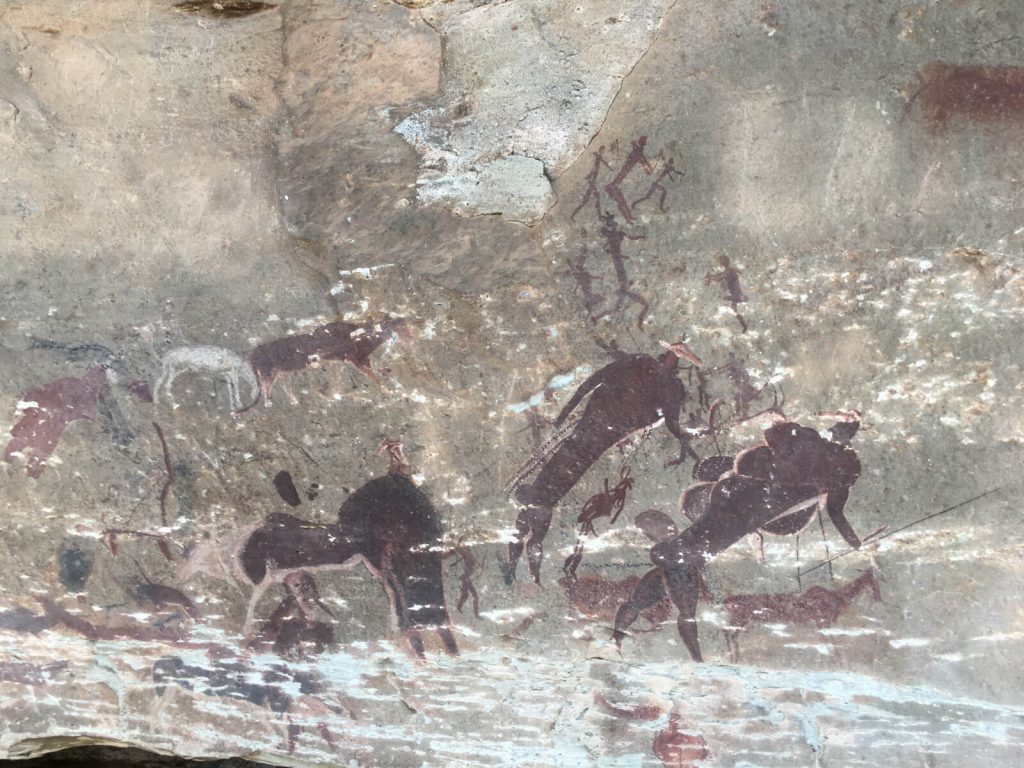

The 2000-3000 year old rock art paintings we visited on this trip in Namibia’s Erongo and Bamberg Parks (and others which two years ago I saw in South Africa’s Drakensberg Mountains) depicted scenes of Bushmen hunters in close community with the animals they hunted, interspersed with scenes that were distinctly shamanic.

Real animals like eland, springbok, giraffes, elephants, lions and ostriches were interspersed with mythical creatures such as mermaids, water dragons, and large balloon-like monsters, which seemed to have emerged from other worlds (often through cracks in the rock surface which might be portals to the underworld or sky).

Many of the human figures are therianthopes – humans with animal heads, animals with human legs and other composite creatures. We are fortunate to have journals and studies by nineteenth century travellers and linguists who recorded long conversations with San and Khoi shamans at a time when Bushman culture and lifestyle was already beginning to change under white settler and Bantu encroachment but yet still retained the memory of its ancient traditions. The meticulous records by Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd and later the writings of Dorothea Bleek relate in detail how the shamans could shape shift into animals, or in spirit form trance travel behind the rock faces to the depths of the earth or the heights of heaven.

There could be communication with animals they relied on for subsistence and a shared consciousness with all the creatures in the Nature they shared. With these clues it seems logical to assume that the hundreds of paintings were religious in nature, that the landscape and dramatic stone outcrops on which they were painted had the sanctity of ancient temples, and that many are actual depictions of the ancient shamans’ journeys and transformations (see https://www.amazon.co.uk/Deciphering-Ancient-Minds-Mystery-Bushman/dp/0500051690/ ).

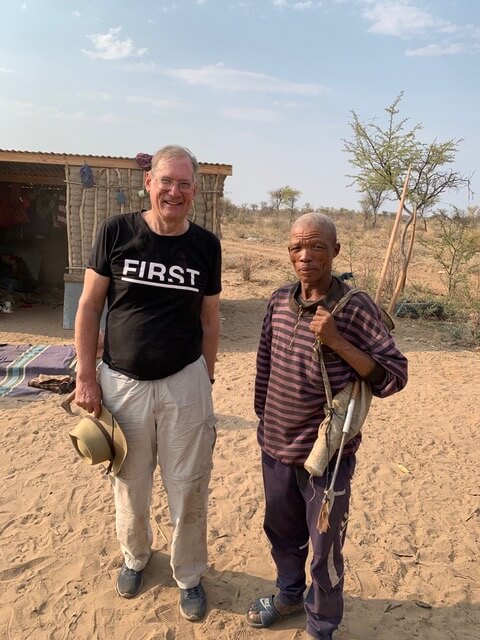

In the countries that we visited few Bushmen express knowledge of such mysteries today. I had the pleasure in the Ngae Ngae Bushman Reserve in Namibia to meet an eminent hunter and tracker, Qui, who, because of his skills, had once been invited to the Paleolithic caves in Southern France to help archaeologists identify millennia-old footprints. He had also visited the rock paintings of his ancestors in Erongo and Botswana’s Tsodilo Hills. “I do not see magic in [the paintings], to me they are pictures of hunts – but the animals are perfect. So are the hunters. We go there to learn from them, how to be good hunters, how to be better men.” I asked him about the Bushman’s traditional ability to communicate with animals. “When I was young the Old People made relationships with animals but nobody can now. Yes,” he said, “sometimes somebody dreams of a herd of antelopes and when they wake they tell us and we hunt them – but this is not frequent now, not like in the old days.” He once knew a man who kept a black mamba that protected his home when he was away, trapping his wife’s lover in their hut so the man could discover his wife’s infidelity on his return “but that was in the old days. These things are rare now. Soon there will no longer be healers living among us and the ability to communicate with animals will cease.”

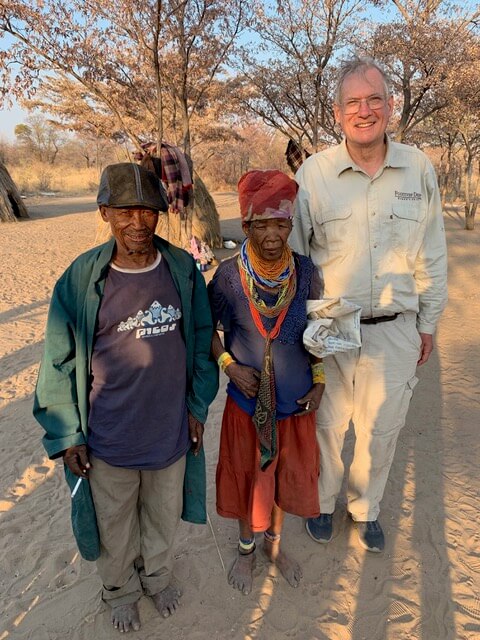

In the large Ngae Ngae Bushman Reserve in Namibia there was only one shaman left. Kuntabo, who joked that he is “older than the trees” (actually he is 85), told me that nobody talks to animals now. “We hunt and kill them! The only exception is the lion, whom we try to soothe to prevent it from attacking us!” Kuntabo told me that the shaman’s duty is actually to talk to God, the Bushman Creator Saang, who has given him powers to heal, and also to keep away mischievous spirits, for example those spirits of the dead who return and try to take away their favorite grandchild. In trance he can dissuade such spirits and tell them to go away. The strong healing powers that God gives him, however, come at a price. In the dance, the chest and ultimately the whole body becomes burning hot, the heat spreading from the diaphragm. This pain is almost intolerable. Most initiates cannot stand it and truly faint, never reaching the state of trance. He pointed jovially at an old one-armed man standing next to him and grinning sheepishly. “He could have been a shaman. He had powers but he was afraid to use them.” He sighed. “You have to be very strong to use the Gift of God, to bear the pain and heal.”

The sad implication was that there were no initiates who would succeed him when he passes away. In South Africa we had met one young Bushman who did have the ambition to be a shaman, but in his community there were no healers left at all, and he had travelled to Namibia to study, probably with Kuntabo. Who in the Ngae Ngae will follow Kuntabo is a question mark, and one which concerns him.

Over the border in Botswana, in the Bushman township of D’kar (near the town of Ghanzi) we met several shamans, the most impressive being Xhara, Gary’s teacher, a man of quiet dignity and calm, with a strong if unstated authority similar to Kuntabo’s. One sensed behind his modest presence considerable power and intelligence. Over the four days we stayed there, camping in the nearby Dqae Qare Lodge, he had the uncanny habit of ‘happening’ to be walking along the same path as our car was taking when we ‘happened’ to be driving to call on him – four times out of four, and on none of the occasions had we informed him we were coming! “Oh, I heard your car,” he would say, with a twinkle in his eye. Dressed soberly in blue, he had been a council official, was still consulted on municipal matters, and one of the days we were there he took us to see some land he is considering developing. In trance dance however his transformation was remarkable; he became a creature of the spirit.

I had the opportunity to question him on our drive back from the veldt and the lost valley full of game that he had found to establish a shaman school. Gary happened to be playing Bushman music on the car CD player. One of the tracks had been recorded at a trance dance. Against the background of the women singing could be heard the male barks of the dancers. Xhara quietly leaned forward from his seat in the back and said, “That’s my voice. I was leading that dance. It is called Eland at Midnight, and it is a very powerful song. My favorite.”

“Each of our songs reflect an animal,” he continued. “As do the movements of the dancers. We imitate the steps of each animal we are honoring in our songs – high steps for the eland and giraffe, the prance of the antelope, the wings and head movement of the dove. We thank the animals for what each brings to our tribe – not only their flesh if we hunt them, and their hides and other parts of their bodies we use in our daily life – but particularly the essence they bring to the dance. We thank them. In turn, the song brings the spirit of the animal to us, in trance it informs us, helps us to identify the illnesses – the colours and smell – and gives us the power to extract the disease or the evil in the bodies of those who have come to us to be healed. It is the spiritual medicine associated with each animal that gives us our power to heal. It reaches us through the pain in the chest that brings us to trance, and has been generated by the song that the women sing to conjure the animal.”

” …the song brings the spirit of the animal to us, in trance it informs us, helps us to identify the illnesses” Bushman rock art at Erongo, Namibia (elephant and shamans)

Gary suggested that the energy produced might be akin to the Chinese qi. That reminded me of how a Mongolian shaman had once miraculously healed a pain in my back, which I had wrenched when falling off a horse by a sacred cairn. He like Xhara in trance had had burning hot hands, which he had laid on my body. He had known exactly where my injury was without my saying a word. I told Xhara this. Also about the love and gratitude this Mongol shaman’s fellow shepherds had shown when they painlessly killed one of their sheep, stroking its head as it died. There was reason to thank the sheep. Its gifts of flesh and skin and wool governed every aspect of their lives, ensuring their survival in the cold of winter. “Your song of thanks sounds like a virtuous circle,” I said. “Yes, it is a virtuous circle,” he said.

I asked Xhara whether he was able to shape shift as depicted in rock art and described by shamans of the past. He shook his head. “The Old People could do so. Not now.” Once he had had relatives in the Tsodilo Hills who practiced shape shifting and other forms of shamanism – “but they are long gone. So are the ones who travel as animals to other realms, and the ones who could snort out evil. “The only thing we still know is the laying on of hands. Only the Old People knew anything else, and now they are gone.”

Qui and Kuntabo had said the same. The secrets had passed away with the Old People. Only tattered threads remained of a way of life and consciousness that once all our human ancestors had shared.

I felt a wave of melancholy. “We in the West lost these skills many centuries ago,” I told him. “It would be sad if they died out here too.”

“Yes,” he said, “The white man should learn again how to live with Nature.” He sighed. “I do believe the Old People knew how to talk to animals.”

That night in my tent I slept badly, Xhara’s words echoing in my head. Living with Nature is the opposite of what mankind is doing now, I thought. We are exterminating it. Climate Change has reached the point of no return. At the same time we are busy trying to recreate the human brain, developing electronic implants that would turn us into cyborgs, without even understanding the mysteries of consciousness – something which Kuntabo’s and Xhara’s and Qui’s forebears understood instinctively. Eminent scientists such as the late Stephen Hawking have warned of the dangers of AI. Our greater knowledge has itself become an existential threat. This is the reality of our world. Politicians have abused our constitutions. Folly has triumphed – and I too had been foolish to think that I could find a culture and civilization anywhere that our modernity had not destroyed.

It really was a bad night. The mosquitos seemed to be inside my sleeping bag. I slept fitfully, and woke about 3 am with a full bladder –the old man’s curse. As I left the tent to relieve myself I looked up at the stars, recognizing the constellations, remembering that I had seen exactly the same sky at the same hour only a night before. Then we had been about to leave a glade faraway in the veldt having just finished a trance dance that Xhara had organised for us. Everybody had been exhausted, but also fired up with an internal energy. As we sat in a ring around the fading fire, I had been recalling the feeling of the dance. I did so again now. I saw Xhara in trance –a titanic presence. I heard again the song, felt the heat of the flame on my belly and knees, and experienced once more the euphoria – and the magic as he and the other two shamans laid their hands on shoulders, heads and feet, drawing out evil and sickness. I recalled again the gratitude on the faces of those they had healed – I was stunned by the sheer unlikeliness of it all, that I had been there to see it, participate in it, experience it for myself and discover it was real. As I stood under the stars I relived it all.

And like the trance for those initiated, I felt a stirring in my belly, rising and burning in my chest, and with it a sense of hope.

Of course it was not too late. My experiences had been real. I had not imagined them. At least some of the old ways still remained. The filmmaker Francis Gerard, who through a contact at Witwatersrand University had recommended Gary as my guide, had told me that when he had filmed Bushman trance dances and hunts for South Africa’s Origins Centre project fifteen years before, it had been in the sad belief that this would be the last chance to record a dying civilization – yet fifteen years on trance dances were still a fabric of daily life. There was nothing manufactured about the joyful shouts of villagers chosen to take part, the spontaneous singing even before it began, the shiver of delight on the faces of old and young when the wood was brought to the fire and the dancers put on their rattles, the awe when the shamans went into trance and began to heal, the sense of wonder and magic that all experienced, participants and bystanders alike.

Much has been lost, but through the likes of Kuntabo and Xhara the shamanic traditions persist, as do the hunting skills of a Qui. A direct link to the world-view of early hunter gathering mankind still survives – if tenuously – which may yet help us understand the expanded consciousness and spirituality of our ancestors that our utilitarian focus in the last five hundred has proscribed.

And according to Gary there are Bushmen tribes in Angola, and even the Congo that have survived its wars and are believed still to be living in the traditional ways. Their shamans may even remember things only the Old Ones knew.

Acknowledgements: For their kindness, hospitality and guidance during this Southern African journey I would like to thank Isaac Swartz and his wife Lydia, Gert Swartz, Ou John and Ricki from Erens Farm in the Northern Cape, South Africa; Shaman Kuntabo, his wife and grandson Khao, Chief Bobo Tsamkao and his sons Leon and Ben, and hunter Qui from Tsumkwe, Namibia; Guide Emanuel from Ai Aiba Lodge, Erongo, Namibia; Shamans Xhara, Xam and Tiger, Kontsa, Jutas and other friends from D’kar, Botswana; managers Greg and Anne Laws, head of office Dieah, along with their brilliant staff and the cultural performance groups at Dqae Qare San Lodge, Botswana; Angie, Katia and Henjik in Ghanzi, Botswana; Shaman Kayake and his wife Boitso and fellow trance dancers in Acagae, Botswana; film maker Francis Gerard; and most of all the Virgil who guided me 5,300 kilometers through a strange, new world, Gary Trower.

A description of shaman dances follows in the next blog post.

Hello, member of LCFN helping the Ju/’hoansi to self manage their Living museums, I know Qui. I visited them twice and we talked a lot about ancestors stories and shamanic transe. And Kxao, best hunter and track reader teacher, also mentioned His identifying with the hunted animal, like an inner track to our animal being. They have a lot of jokes and stories about the time human were just another species. Gary Trower just saw some unusual old representation of one their myth about beginning of life we found with Kxao. We hope that it will find the right interest. Thank you.

Fascinating to read. What a joy! Don’t be downcast Adam. I believe the spirit world lives on regardless of the follies of modern man and we can rediscover what is lost through being open to communication and seeing and listening, as you are doing. I believe it was deliberate destruction of ancient spiritual knowledge that killed it off, not carelessness or commerce. When the Romans manufactured Christianity for example they slaughtered the Druids and the Celts so the new religion could not be exposed as the fraud that it is, and the real spiritual knowledge of Izas could be hidden. All libraries were burned and those like King Izas who resisted were killed or imprisoned (in Chester til he died). The Dead Sea Scrolls show that he and his followers knew how to communicate using ritual extra-dimensionally, and they realised that their knowledge would be destroyed by the Romans, who communicated extra-dimensionally with Satanic type of spirits and wanted all contact with spirits of goodness eliminated.

In the Philippines I meet a healer called Michael who has taught me how to cure pain in myself and others, and destress the mind and body. He lived with the Mangyan on Mindoro as a child when his gold-prospecting father gave him to the natives to look after for a year. He offered to show me their secret ancient sites and rituals but as yet I have not done so. We meet at a cafe near our house. I should be inspired by your efforts to do so.

Our young daughter (1) and two boys (12 and 8) keeps us busy and other mundane things while we are there. My friends in the Phils are sadly now very old and not up to much. I will follow Michael the healer up on our next trip and try to persuade Shane that we might head that way.