Rosemary Sutcliff’s historical fiction

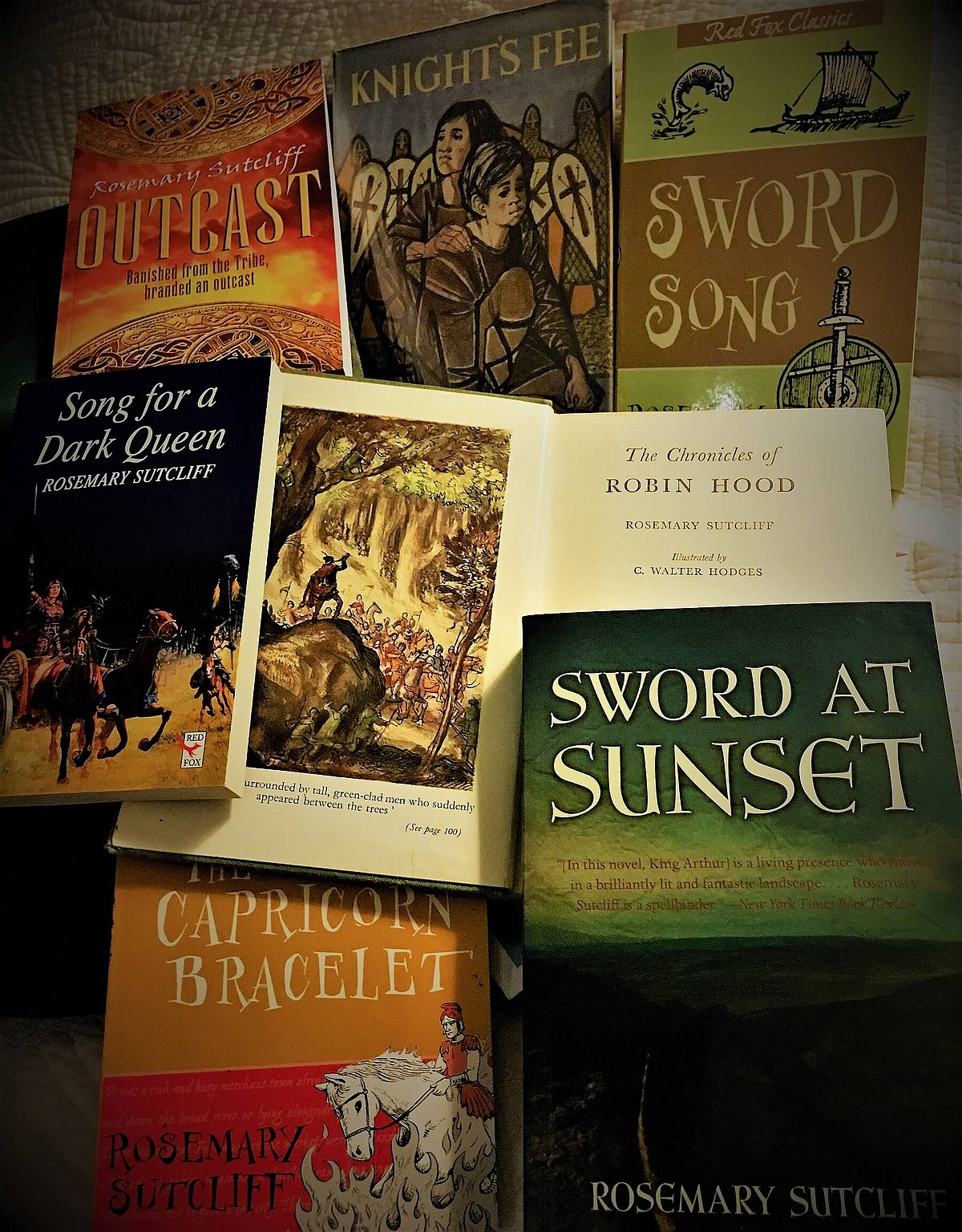

When, back in 1962, aged nine, I was sent off to boarding school in England, my grandmother gave me a book called “Warrior Scarlet” by an author called Rosemary Sutcliff. It was an adventure story about a boy with a crippled arm growing up in Bronze Age Britain, overcoming his disability and hardships and becoming a hero of his tribe. For a small boy with a speech impediment suddenly pitched far away from parents and home into a scary new environment the other side of the world, this adventure tale of a boy just like me who had lived two thousand years ago inspired and helped me to come to terms with my new school. I also began to learn something about the early history of my country, and that gave me a sense of belonging and identity. I developed a great love of historical fiction, and of Rosemary Sutcliff’s books in particular, which I began to collect. Her “Chronicles of Robin Hood” made real for me a world in which that great legend might actually have lived. I learned about the Norman Conquest from “Knights’ Fee”. My first understanding of Shakespeare’s life and times came with her story of wandering Elizabethan players, “Brother Dusty Feet.” I have loved history ever since. For me, as with Sutcliff, it always begins and ends in a story. Tens of years later I published my own first novel and no surprise it was historical fiction.

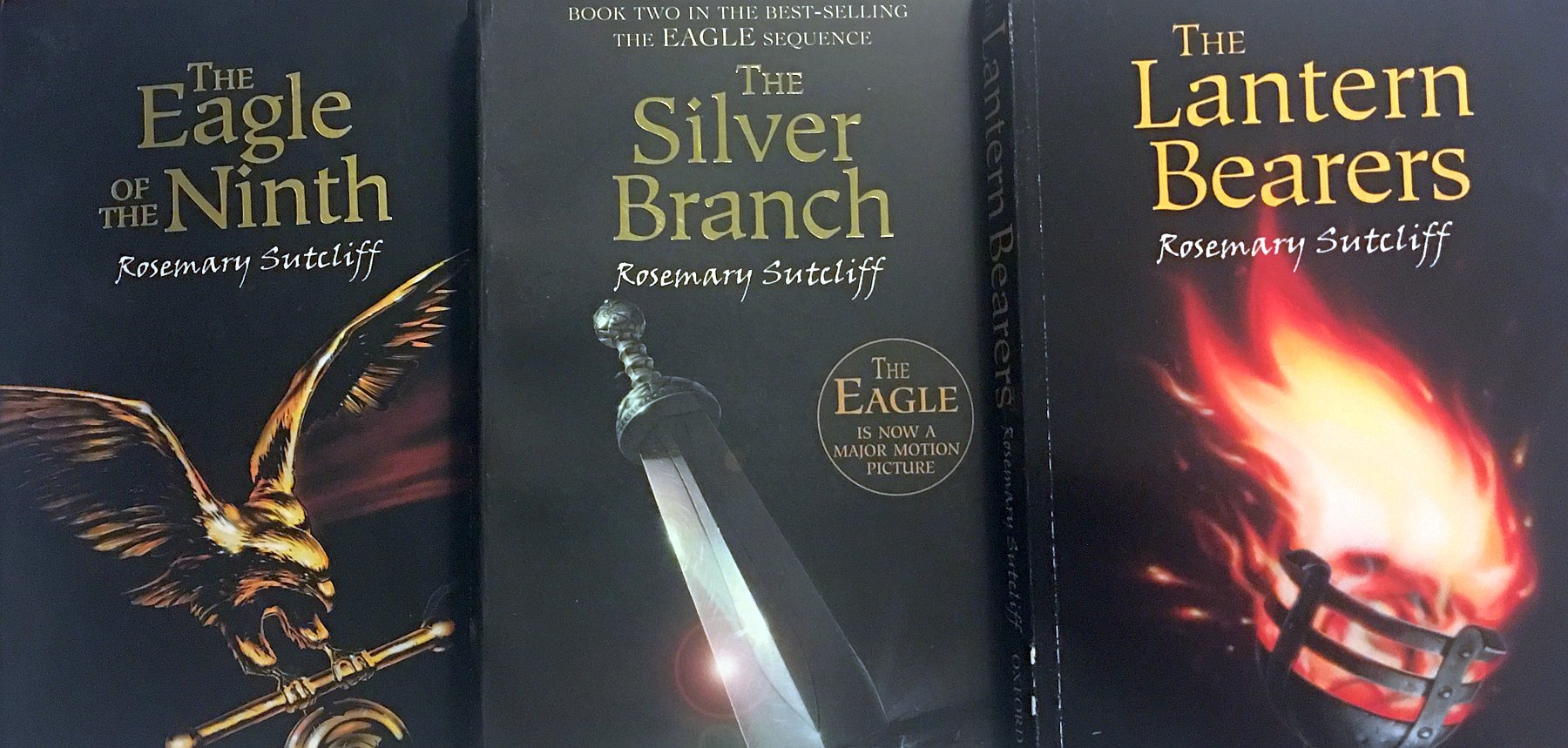

Today Rosemary Sutcliff is best known for her novel “The Eagle of the Ninth.” It is a classic adventure story. A young Roman centurion, Marcus Aquila, invalided out of the army, attempts to regain his own and his father’s honour by travelling into the barbarian lands of the far north beyond Hadrian’s Wall in order to recover the lost standard of a defeated Roman legion. Accompanied by his servant, the ex-slave, Esca, a Briton of his own age, the young Roman, in the guise of a quack doctor, travels among the wild Pictish tribes, and overcoming terrible dangers, returns with his Eagle. For excitement, Rosemary Sutcliff’s novel ranks with the best adventure tales in English literature – in her description of Marcus and Esca escaping their pursuers over the Scottish moors she out-Buchans Buchan’s “Thirty Nine Steps”. She has an uncanny ability to evoke the sights, the sounds, even the smells of the ancient past. Her poetic prose leaves images of landscape that linger in one’s imagination afterwards.

Yet the “The Eagle of the Ninth” is more than a thriller. Marcus’s journey is also a voyage of discovery. He sets off on his journey a Roman proud of his superior civilization, but through the book he is entranced by the extremes of landscape and weather that slowly evoke in him a love of the soil of this strange island he had come to as a conqueror. Behind the barbarities of the “painted peoples’, he recognizes decency and honour in his enemies. Respect replaces hatred. Esca, reduced by circumstance still has the pride of a warrior and hunter and skills that excel Marcus’s own. Over the course of the book servant and master become blood brothers, equals and friends. And Britain becomes Marcus’s home. At the end of the book he marries a British girl, sets up a farm, to be run not by slaves, but by free men, Roman and Britons working together.

In trendy modern parlance one might say that Rosemary Sutcliff anticipated in “The Eagle of the Ninth”, and in the two books that followed, the “diversity” that created the nation that became Great Britain. Her stories are about her own homeland, and reflect her pride and love for her country and its history, but her larger theme, that basic human decency and honour can ultimately reconcile all warring tribes, and bind them into a whole, makes her work universal. Chinese fans of the martial arts stories of the late Louis Cha Jin Yong might be surprised to find that some of the noble strains to be found in his works can also be found in the books of his wheelchair-bound English contemporary author the other side of the world.

The second novel in the trilogy “The Silver Branch” is set 100 years after the events of the “Eagle of the Ninth” when Rome, beset by civil wars, is losing control of its far away colony. It is another exciting adventure story in which a centurion descended from Marcus Aquila and his doctor cousin “go underground” to form a ragtag army of fellow Britons to overthrow an evil usurper and his Saxon mercenaries who has murdered the rightful emperor.

In the third book of the trilogy, “The Lantern Bearers”, another century has passed, and Rosemary Sutcliff, in keeping with a much darker period of British history, tells a much darker story.

In the third book of the trilogy, “The Lantern Bearers”, another century has passed, and Rosemary Sutcliff, in keeping with a much darker period of British history, tells a much darker story.

As the book begins, the last Roman Legion departs Britain’s shores. Civilization lies abandoned and defenseless against the raids of the savage Saxons whom a weak British king has invited in to protect him from the hatred of his own people. Meanwhile the rightful ruler, Ambrosius, with his small army, is holding out in the northwest of Wales. The Saxons and Jutes have already taken land from the pliant king and plunder where they can, whilst their leader Hengest plots to seize the weakened kingdom for himself. The hero of the story, Aquila, has watched the legion go. He has deserted the Eagle because his home is Britain and he cannot bear to be separated from the farm that has been his family’s for 300 years – but the farm is burned by a war band of Saxons, his father and retainers are brutally killed, his sister is dragged away on the shoulders of a warrior and he is enslaved. He expects never to see Britain again, but two years pass, Juteland is barren, and his masters decide to settle in Britain where there are richer harvests. In a Saxon camp by the Thames Estuary he meets his sister who is nursing her baby by the Saxon who abducted her and has since married. She helps him escape but he can never forgive her for choosing to live with the barbarians. In his view it would have been better had she died. With nothing to live for, hating himself and the world, he takes the advice of a kind hermit physician who removes his slave collar and chains, and decides to throw in his lot with Ambrosius in Wales.

So begins this story of hatred, revenge and ultimate redemption in a book that is much more adult than its two predecessors. Rosemary Sutcliff spares the reader nothing in her descriptions of the cruelties of war, and she includes in savage detail all the betrayals, murders and tragedies that are part of the history of this period. The psychological portrayal of the emotionally scarred and ruthless cavalry leader that Aquila becomes is not attractive – he is a terrible husband to his wife – the daughter of a Celtic chief whom the British king Ambrosius wants to bind into an alliance – and later, a distant father to his son, yet Rosemary Sutcliff never lets the reader entirely lose sympathy with this dour, broken man, whose military skills have made him a leader of the resistance against the Saxons. Slowly the tides turn and hope returns. Ambrosius’s nephew, a young cavalry genius, Artos the Bear, inspires the resistance troops, and the Saxon king is soundly defeated at a great battle. Aquila, leading another wing of the army, watches his son follow this new leader and feels he has lost him. He wanders the woods after the battle, and stumbles over the body of a wounded young Saxon, who is the spit image of his sister. He realizes who he must be – but soldiers of his own army are ruthlessly slaughtering Saxon survivors. Aquila remembers his sister. Here is perhaps a chance of redemption for his wounded soul – if he can only save her son, his nephew, now one of his bitterest enemies.

The last book of the trilogy is no longer a children’s adventure story. Rosemary Sutcliff in “The Lantern Bearers” is describing a life that has fallen apart, one of bitterness and sorrow, where there is no guarantee or likelihood of a happy ending. It is the world as its worst – abandoned of everything except hope. However, in the figure of the good physician, and the small court of Ambrosius, hope does remain, and in this last beautifully conceived and written volume of the trilogy, Rosemary Sutcliff’s theme remains strong, perhaps stronger: however deep the hatred, however cruel the war, however unforgiving the two sides, bonds between enemies can be made. Virtue and honour, even family ties, can be recognized. There is a possible future, Rosemary Sutcliff affirms, in which reconciliation may occur. As a slave in Juteland, Aquila despite his hatred gives grudging respect, if no love, to the impressive old chieftain of the barbarian clan, who embodies the harsh virtues of his race. It is a small recognition of common humanity. By helping his nephew and forgiving his sister, he might find a way perhaps to forgive himself, and in so doing regain the love and respect of his own wife and son.

Rosemary Sutcliff

Rosemary Sutcliff of course knew her history. There were decades of war still to come, and ultimately the Anglo Saxons, as they became known, triumphed – but Britain over time influenced and converted its conquerors. Centuries on, it became the Anglo Saxons’ turn to carry the torch of civilization, and, as new forbears of the British race, to defend their island from the even more terrible Vikings. As the Romano-Britons had had their King Arthur who held back for a time the Saxons (Artos the Bear in Sutcliff’s books) so later the Anglo-Saxons had their Alfred the Great who for a time held off the Danes. Resistance might ultimately end in defeat, but the British, whatever their origins, assimilated their conquerors, as in China, over even longer periods of history, the Han people assimilated their own barbarian conquerors, who adopted China’s civilization, values and culture, and became Chinese. Such are tides of history. The lanterns of civilization are never ever totally extinguished.

One of my very favourite books!

thanks adam, I’ll read it!