Over the last few years I have fallen into the habit of making a pilgrimage each autumn. These have included traditional pilgrim paths such as the 1000-year-old Roman Catholic Camino to Santiago di Compostela in Spain and the even older Shinto Kumano-Kodo in Japan. Last year I went further back in time to follow an Aborigine song line in the Kakadu National Park in Australia and, from there on to the mysterious and very ancient rock art sites in the Kimberley Range of Western Australia. I have defined pilgrimage to mean a hard walk (penance) followed by a visit to a ‘cathedral’ (spiritual sanctuary). Over these years my journey has taken me from sites related to Monotheism to Polytheism to Shamanism. This year I again took my pilgrimage back 35,000 to 40,000 years, and visited the Paleolithic Cave Paintings in the Lot and Vezère and Dordogne regions of France.

To be truthful, when I first embarked on these adventures, I had more interest in healthy exercise and weight loss than spiritual purification, but as I found, the very act of taking paths where thousands have trod over the ages and the enforced meditation that comes from the monotony of tramping hours through countryside redolent with such associations has a way of bringing the metaphysical closer to mind. A window seems to open into the synchronous. One feels aware of the life force around one, of which oneself is but a tiny element. It is as humbling as it is inspiring. Wandering a dappled path alone on a sunny afternoon, cirrus drifting into blue sky from the mountain tops, the idea of a universal consciousness does not seem so outlandish. There do indeed appear to be “tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stone and good in everything.”

Shakespeare was being gently satirical, but on the pilgrim path, extraordinarily, one does find oneself suddenly and unexpectedly plugged into an energy that like water or electricity appears to link one to animal, mineral and vegetable, and even at times the supernatural. It is as if, in an altered state, one has had a glimpse of another dimension, only a thin film separating it from our own. Of course when one rationalizes in the evening, over a drink or a steak, one will attribute the experience to tiredness; one tells oneself that somehow one’s imagination has been on overdrive… Yet these inexplicable experiences do take place with puzzling regularity. There may be nothing mystical about them but one can’t deny they happened. Or forget that they happened…

And it is not as if there is a lack of precedent in philosophy. My friend, Laurence Browne, a companion on some of my journeys, an expert on Synchronicity, author of The Many Faces of Coincidence, writes about the mediaeval Unus Mundus and the mystics who could glimpse into a spiritual world parallel to our own. Meanwhile, in popular folklore there was the Land of Faerie, a dangerous realm which one entered at one’s peril. Certainly we have the idea of other worlds imprinted in our psyche from folklore, and they are the staple of children’s literature – even though adults are nowadays expected to put such fantasies behind them. Adult fantasy – and we have it – is usually respectfully cloaked as allegory or science fiction (much to the chagrin sometimes of the real scientists who protest that films based on quantum physics parallel world theory such as The Matrix or Inception have misunderstood the implications of the double slit experiment!)

But even the most arrogant of scientists, unlike the irrepressible Mr Toad, will admit that they do not “know all that there is to be knowed” and acknowledge that there is one lacuna in our collective knowledge that still defies rational understanding. Since Reason overtook the world in the Eighteenth Century, our sages have mapped out the universe and written the laws of physics and everything else. They are now launched on the last task left before we can claim godhead: artificial intelligence and the modeling of the human brain – but they have not been able to define the most basic element of consciousness – even though it is something experienced by every human and animal, and even, we are told, by trees. Consciousness is something we take for granted. It snaps on when we wake, and even operates in our dreams; it is what defines us as individuals, yet no one can explain how it works.

There seems to be an academic consensus that consciousness must be an attribute of the brain. Perhaps a majority of scientists would be comfortable with a solid material explanation that places this inconvenience safely inside our bodies, and firmly out of the realm of spirituality. How comforting it would be if it could be explained away like cognition is by the interplay of electrical currents connecting synapses in different portions of the cranium. Yet, inconveniently, experience seems to indicate that there are times when extra sensory perception occurs outside individual brains, not only between humans but also between animals, and between humans and animals.

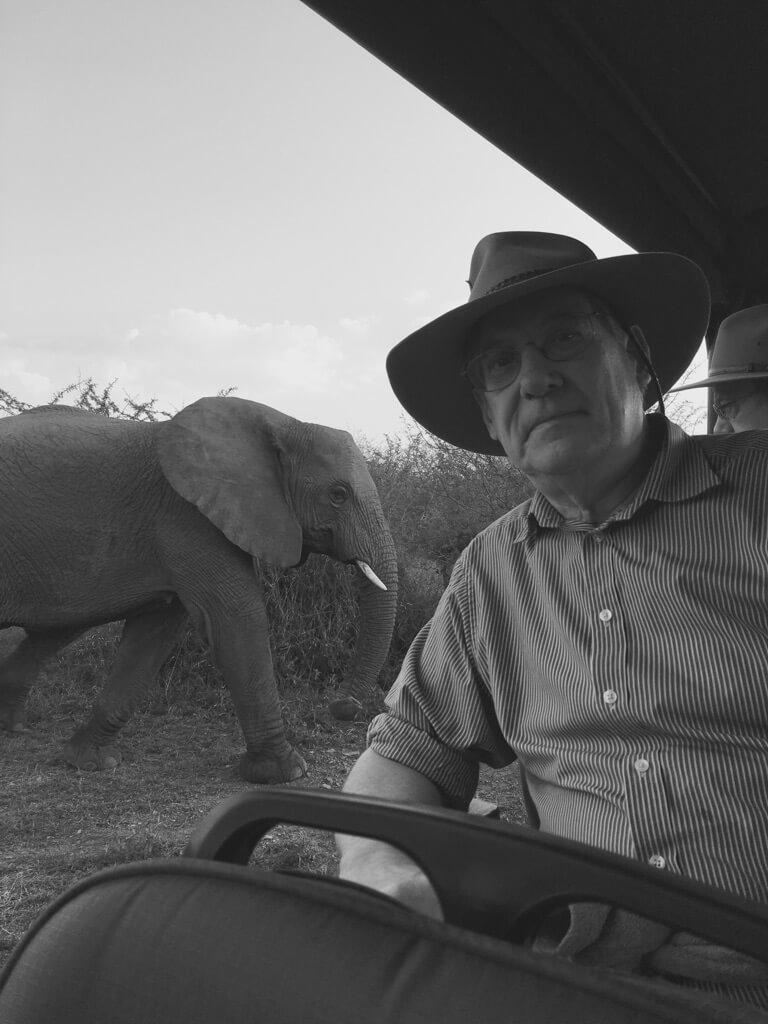

Rupert Sheldrake has written a book about the extraordinary ability of dogs and cats to sense activities of their masters hundreds of miles away. Anybody who has read The Elephant Whisperer will know of these magnificent creatures’ uncanny ability to communicate over vast distances. After the death of the author, Lawrence Anthony, who in his book wrote of his warm relationship with the herd of wild elephants that he had rescued and brought to his sanctuary of Thula Thula in South Africa, his family, arriving at his favorite lake to scatter his ashes, were as amazed as they were touched to find that the elephants had lined the opposite bank, waiting to pay their last respects to their friend. Consciousness it seems is a medium that eschews boundary of body or even specie, and has a language of its own. And it is only our materialist world that wants to box it.

The ancients had no problem defining collective consciousness. A Hindu or Buddhist celebrates it as the larger spirit of which we all form one part. It is everywhere. It is part of the living universe. It IS the living universe. The few hunter-gatherer tribes left in the world would agree. And I imagine that our ancient ancestors would only look with pity on civilized western people who only believe what they can rationally explain as scientific provable fact. How are we better off, they might ask, that we no longer know how to dance to the rhythm of the stars and the earth, or sway with the trees, or thank the killed deer that has allowed itself to be sacrificed for our meat? They might wonder how our hunters’ senses have atrophied and how we have lost our ability to commune with Nature. And I do not think they would understand at all how as rational beings we have allowed the world to enter the existential state of crisis in which we find ourselves today – and yet still consider ourselves civilized.

And over the four years in which I have been wandering, I have also been wondering. What distinguished the hunter-gatherer societies from our own? We know that physically and cognitively our 50,000- year-old ancestors were no different from ourselves. Take off their furs and put them in denims and we would not be able to distinguish them in a crowd. But how did they think? Did they view themselves even then as the lords of the planet, its resources their birthright to plunder with all the ingenuity and violence that their advanced cognitive powers could bring to bear, organizing even then the extermination of the wild life around them? That is the picture that Yuval Noah Harari draws in his rather wonderful and very misanthropic review of human history, Sapiens, explaining from earliest instances how we became the self destructive predators we are today. Or were they after all what we would like to think of them as – attuned to the world in which they found themselves, playing their ecological part with all the other good animals in the harmonious dance of Nature (no doubt strumming on their didgeridoos or fluting on their reed pipes a primitive version of Elton John’s Circle of Life)?

Well who knows? There seems little consensus among paleontologists, who are finding every new archeological dig a challenge to their preconceptions. For me the mystery seems very much tied up with consciousness, or has become so after my pilgrim walks. I have seen rock art now in South Africa, Australia and France, dating back thousands to tens of thousands of years, to the Ice Age in fact, and I have been stunned by its beauty and apparent reverence of Nature. The upshot was that a curiosity formed and took shape in my mind, and my interests and my reading began to focus on the spiritual beliefs of our oldest ancestors (as far as we can tell of them) in a sort of amateur quest to understand the sort of consciousness which linked our hunter-gatherer forbears to the Nature around them, and the spiritual beliefs that are reflected in their art.

I suppose at the back of my mind I am thinking, can we learn something that may bring common sense back to our materialist world, doomed, it seems, either through climate change, nuclear proliferation, AI, populist politics or any of the other existential threats that greet us daily in our newspapers? Or at least, can I find something that makes sense to me?

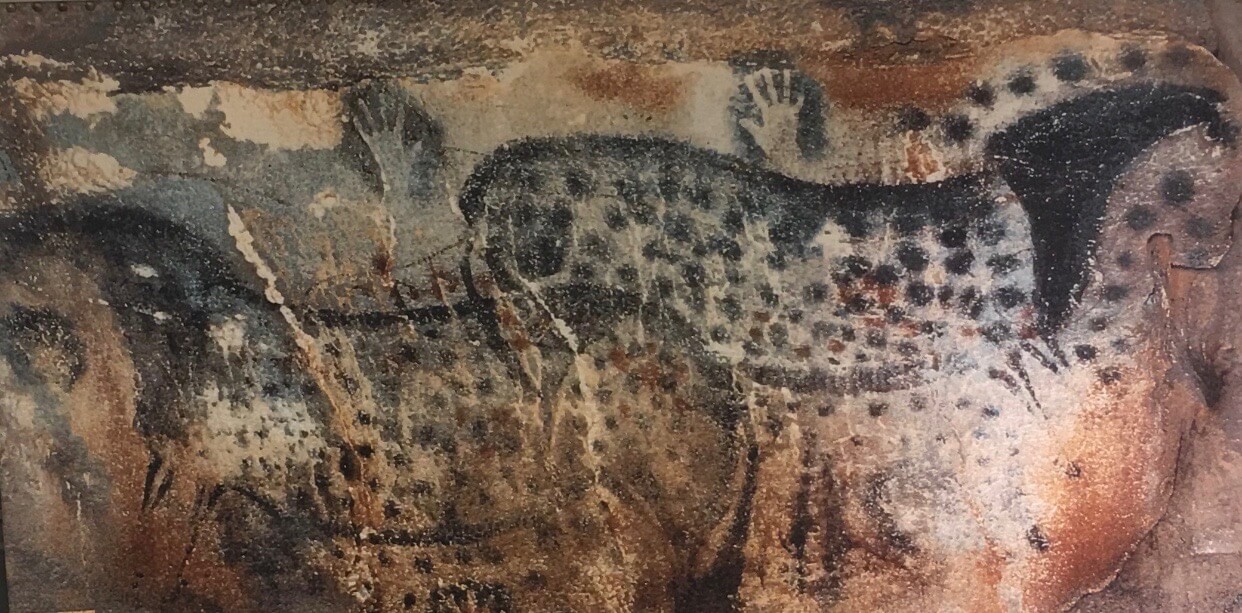

Guided by my good friend, the film maker Francis Gerard, who has spent much time with the San people in South Africa, I have been reading the excellent works by the South African paleontologist David Lewis Williams, who, though himself a true scientist and no believer in religion or the supernatural (indeed his books seek to explain religious phenomena as a function of the brain) has nevertheless come up with perhaps the most compelling explanation of what primitive man believed. He spent much of his life studying and explaining the mythology of San (or Bushman) Rock Art, benefiting from the accounts of shamans who allowed their beliefs, their cosmology and their practices, to be recorded and transliterated during the 19th century by interested missionaries. He then studied the much older Paleolithic caves in France, and found that the theories he had developed in South Africa which applied to San art applied equally to the much older cave art in France. In so doing he directly challenged the Structuralist approach that earlier paleontologists had been using to explain Paleolithic art, and convincingly demonstrated that whatever else our unknown ancestors happened to be, the likelihood is that they had Shamanic beliefs. Like the San, in fact, who believe in a spirit world beneath the rock, which the shaman can access by taking on one of the animal spirit forms and in an altered state enter and perform magic for the benefit of his tribe. View the French and Spanish caves in this light and all makes sense. The animal spirit forms come out of the rocks – the painters with great beauty and skill highlight what is there. In the flickering torch light of these dark womb-like caves the spirits move and re-form. It is a weird and dangerous world the shamans and their initiates enter but the journey (in altered state induced by trance dance or drug) makes them one with their universe. The power they gain from the animal spirits helps them with their hunting. The knowledge attained in their equivalent of the Unus Mundus allows the tribe to survive.

So that is why in early October of this year, following a route chosen for me by a friend who had come that way the year before, I found myself climbing the calcite hills above the Célé valley. I was again travelling on the Camino that leads to Santiago (the Chemin de St Jacques as it is called in France) but this time the penance path was taking me to a different sort of sanctuary, honouring an older religion than Christianity or any of the Monotheistic religions, and reflecting the beliefs of the people who lived and worshipped 35,000 years ago.

And as I had hoped, past and present converged, rolling through many figurations of time. Starting at the beautiful mediaeval town of Figeac (famous now as the birthplace of Champollion, the man who deciphered the Rosetta Stone) I walked for six days through beautiful autumnal countryside, blessed but for the final day with the finest of weather. The comfort of the chambres hôtes where I stayed each night, not to mention the excellence of the fare and the kindness of my hosts to a complete stranger, could not be matched. Without exception I was made to feel like a guest or friend. For a hiker, entering these rugged hills and valleys following the winding river, it was like stepping for a while out of the world. In fact during the six days I spent on the road I came across only two shops, and one restaurant and they were all in the one town of Marcilhac, which I reached on the fourth day. I lingered there. It was a fascinating place to visit, containing the ruins of a magnificent abbey, broken walls and melancholy pillars, with only its grand church functioning – it was being lovingly restored for the third time, the monastery having been sacked during the 100 Years War of the 14th and 15th Centuries, the Religious Wars of the 16th Century and again the French Revolution in the 18th Century. It is a wonder of its kind, as was the convent in the village of St Eulalie I had passed two days before – also abandoned in the French Revolution. My journey was designed to take me to an ancient past but every part of this fascinating landscape had historical resonance and romance, a tapestry that had been stitched through all the ages.

Almost immediately I felt that this small portion of the Chemin de St Jacques throbbed with that same charge of special energy and sanctity that I had experienced before on the Portuguese and Spanish Camino. It was not only that it had been a pilgrim way for centuries. Whether it was the mysterious tangled paths though woodland or heath or the presence of the large white calcite cliffs, I sensed a weird and very old magic deep within the countryside itself. Its geology was ancient, the wind that sighed through the rocks pungent with prehistoric fugues. This area, I discovered, is known as the black triangle of France because it is one of the few places in the country where the sky at night is clear of light pollution and, as in the Australian outback, the stars feel close enough for one to reach up and run a hand through the Milky Way – and again I sensed as I tramped and climbed over the landscape that narrow film separating this world from a metaphysical other world parallel to ours where strange coincidences are the norm. More than once I found myself fantasizing into romance. Once in a wood, lost, like Sir Bors in the Morte d’Arthur, I came to a fork in the path, and sat in the flowery, russet glade wondering where to go next. Suddenly I heard laughter and two village girls walked by. They were dressed in hot pants and held iPhones, but in my Arthurian mood they could have been damsels sent by Morgan la Fay. As one, they gestured behind them, and giggling tripped on. I walked back and immediately came across a snake crawling across the path. It eyed me. I eyed it, then I stepped over it and it wriggled away. Immediately I saw the mark of the pilgrim path I should have taken. I felt that I had been supernaturally guided…! Of course it is nothing but normal for snakes to be found in woods or for villagers to show the way to a stranger, but for me, as I walked down the church-like lane through the trees afterwards, it had been an incident full of arcane symbols. Such are the thoughts you have on Camino!

It was late in the season and there were few pilgrims left on the road. I only really met two during the whole journey, but one night, in the most beautiful village of Brengue, I shared a dormitory with six divers – those intrepid underwater adventurers and cavers who go into the deepest of underground rivers and flooded channels (the country here was full of these subterranean marvels) for – “What?” I asked one of them over dinner, a thoughtful businessman from the Loire, “What is it that attracts you to these dangerous places?” They were entering another world, he said, a parallel one of almost unbearable beauty which will give you the most exalted of experiences or kill you; it is courage, strength, belief and skill which can get you through the dangers, and when you return to the surface again, re-entering reality, it is as if you have experienced an altered state. I wonder if that answer would be any different to what a Paleolithic or San shaman would in essence have told me if I had asked him about his trance journeys into the caves or behind the rock wall where the spirits dwell. This modern Frenchman had in all essentials presented me with a 21st Century, high tech parallel of the shamanic journey. Again it seemed synchronistic, an echo of the Unus Mundus, an affirmation of the sort of quest I was on. I felt this encounter had been rigged to prepare me for the caves!

The last day of the walk I came to the cliff hanging town of Cabrerets – houses built on ledges on the rock face which once no doubt had served as shelters for Magdalene man to huddle with his family against the cold, and after a coffee with one of the two pilgrims whom I had randomly met again for the third time (all these synchronicities!) I climbed the steep path beyond to the ancient cave of Pech Merle, with its stalactites and rock etchings and paintings. This was my reward, the ‘cathedral’ I had been heading for, and of course, it was stunning. There on one side of the large cavern were the famous dappled horses, and in other crannies appeared the outlines of huge, prehistoric aurochs and mammoths, and in one section a human figure, which the guide (taking the literal and Structuralist party approach that still dominates cave art explanations) described as possibly representing a man stabbed by many spears, a sacrifice perhaps. But I remembered David Lewis Williams, and thought of these ‘spears’ as energy lines and recognized this figure for a sorcerer, a shaman about to transform into one of the spirit creatures depicted on the cave walls….

The last few days of my stay I hired a car and drove north to the Vezère River Valley, a tributary of the Dordogne, which is another area of calcite cliff that used to provide shelter for the Paleolithic hunters and gatherers and contained around them a vast number of caves, painted and unpainted. The painted ones include some of the best in France: Cougnac where mysterious outlines of great elks emerge from forests of stalactites; Lascaux, described as “ the Sistine Chapel of Paleolithic Art” with its hall of bulls (and other animals) running helter-skelter towards a hole leading to dark, narrow tunnels into which only initiates had access; the Font du Gaume with its buffalos that seem to come out fully formed and alive from the natural rocks; Roussignac where one takes a subterranean train several kilometers through caverns engraved with mammoths; Les Combarelles, a deep narrow cave etched with the most lifelike lions and horses, and women’s bent torsos. There is a huge sexual element here, many of the sorcerers have erections and often there are ‘v’ outlines of vaginas etched on the rock – but this is not surprising, the cheerful and very open-minded guide of the last cavern I visited, La Grotte Prehistorique du Sorcier, told me (no Structuralist she):“These are temples, full of magic, where the sorcerer transforms and deals with the spirits of animals on whom the hunters rely on for survival, but they’re also wombs, these long narrow tunnels, where the deepest mysteries are explained, the generation of life.”

And I came away from it all, my head spinning with wonder and new ideas, ever more convinced that these marvels from the past have lessons for us now. The synchronicity just buzzed. I sensed a purpose. Maybe a book will come out of this one day, maybe not – but I feel I’m blundering towards something!

Chambres d’hôtes en route de Voie Célé

Day 1: Figeac to Mas de la Croix (Beduer) – 12 km

Chambres d’hôtes Germier

Jeanne et Christian Germier, Tel 05 65 11 40 86

Day 2: Beduer to Sainte Eulalie – 12 km

Chambres d’hôtes Les Anons du Célé

Enza et Paul Pezone, Tel 05 65 50 2657

Day 3: Sainte Eulalie to Brengue – 10 km

Gite La Brengoise

Claude Lecompte, Tel 09 63 26 31 46

Day 4: Brengue to St Marcilhac – 11 km

Chambres d’hôtes Chez Tateene

Genevieve Mignat, Tel 05 65 11 63 68

Day 5: St Marcilhac to Sauliac-sur- Célé -9 km

Chambres de Marianne

Roland et Marianne Ryckelynk, Tel 06 16 59 36 59

Day 6: Sauliac to Cabrerets / Pech Merle – 10 km

Taxi back to Figeac

Le Manoir Enchanté, Tel 06 16 59 3659

Chambres d’hôtes dans la Vallé de Vezère

Days 7-10: Based in Les Eyzies-de –Tayac

Chambres d’hôtes Le Menestral