Last Monday my Shanghai colleague, Eugene Liu, and I escorted a 93-year-old Jardine veteran, Mr S C Fong, a former senior manager of the Airways Department, back to his old office at 27 The Bund. Mr Fong is probably the last person left alive who worked there when it was the headquarters of Jardine Matheson & Co.

The land – Lot 1 – with its view of both stretches of water at the bend of the Huangpu River had been bought by Jardines in 1843 when foreign merchants first set up trading posts in this then tiny East China port. As a large city grew up behind the initial factories and go-downs, Jardines established the site as its China headquarters. It was to remain such for a hundred years.

The style of the building changed from colonial bungalow to city mansion, and finally became the great, granite-blocked edifice built in the early 1920s at the height of the firm’s commercial power. Its go-downs, crammed with silks, tea, tung oil, frozen eggs, machinery, wines, whiskys and a vast range of trading goods, stretched back a block behind it to Sichuan Road. Jardines was then the richest trading company in China.

During the Second World War the Japanese occupied the building and added a floor on top. It was recovered by the firm in 1945 and restored to its former state – that’s when Mr Fong first worked there – only to be lost again four years later, this time permanently, when the Communists forced Jardines to dispose of its assets and 200,000 staff on the Mainland. Jardines’ departure, negotiated by the then ‘Taipan’, Sir John Keswick, took four years, after which 27 The Bund was taken over by the newly formed Shanghai Foreign Trade Commission.

The venerable building remained government offices for fifty years. The white roof structure built on top did nothing for its looks. It became shabbier and shabbier. Then, in 2008, No 27 the Bund was given a new lease of life when it was taken over by the Roosevelt China Investment Corp. After extensive renovation it was transformed into the elegant House of Roosevelt, containing a club, offices, bedrooms, restaurants and the largest wine cellar in Shanghai.

Three months after its opening, the House of Roosevelt had invited Mr Fong back so he could tell them what it was like in the old days.

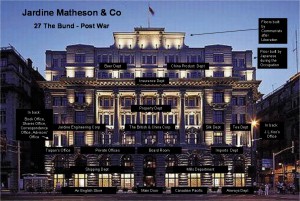

Mr Fong knew the building well. He had joined Jardines in 1944 in its wartime headquarters in Chongqing, where he had been working with Sir John Keswick on the war effort. After the firm’s return to Shanghai, he was employed in several trading divisions before settling into the new Airways department. He remembered the layout of the building exactly. He came prepared with a chart he had drawn, showing where all the different Jardines departments had been located.

Mr Fong is frail now and hard of hearing, but one would not have known it seeing him stride, wheelchair disdained, along the familiar corridors, his eyes gleaming with his memories.

He told the Roosevelt manager who met us that the outside of the building today looked in better shape than it did when he worked there, because there had been much wear and tear during the war. He looked at the entrance hall and the great staircase rising from the first floor (Mr Fong still called it ground floor in the old English/Jardine style) and said it was all exactly as he remembered – except for the door onto the street, which in those days had been gleaming copper.

We were ushered into the former directors’ lift – the lift inside is new but the art deco façade and doors were as Mr Fong recalled them – to the second floor (first floor as was) which Mr Fong said had been occupied by the Shipping and Cotton Mills Departments. Today it is the House of Roosevelt’s wine cellar, with racks of bottles and a tapas bar. Mr Fong noted that much of the wooden floor was original as were the square white pillars. He told Eugene Liu that this was where his father had worked.

The third floor (second floor) is now the preserve of the House of Roosevelt Club (very exclusive – membership only). In Jardines time this was the Directors’ floor. The Club managers were anxious to get Mr Fong’s confirmation that they had accurately restored the corridor where the directors’ offices were located. In most of the public spaces they had replaced the scuffed tiles with green marble, but here they had laid down black and white mosaic in what they thought was the original design. Mr Fong examined it and nodded, saying, yes, this was exactly as he remembered the flooring of all the corridors in the building. He smiled when he entered the great board room because the oak panelled walls and floorboards (imported wood from Britain) had not changed. Even the colours were the same. He immediately recognised the subjects of the two painted portraits on either end of the room: “Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt,” he announced in his clipped, old-fashioned English. In Jardines days, he explained, there were no portraits – only one half-wall of photographs. Nor was the table as large as the banqueting one that now runs the length of the room. There was only a small conference table facing the window in the far quarter of the room. The rest of the room was bare and used for entertaining. He had a memory of several sea captains from Jardines ships with their backs to the blaze in the fireplace, smoking big cigars….

Along the corridor we passed directors’ offices. This one belonged to Mr Barton, he said, this one to Mr Lennox. Peering inside he noted with approval that the frosted glass walls that stretched up to the ceiling on each side, separating the offices one from another, were still in place. “Just as it all was,” he said. “Well, except for the dining table. They were offices then – with desks, and metal cabinets full of papers.” There was no other furniture, he added. No chairs. Visitors did not sit down in front of the directors. They stood. That was so no time was wasted with idle conversation after the business had been discussed….

Our host from Roosevelt asked about the sliding hatches on the inside of the office doors. Mr Fong explained that the hatches were for the directors to look out of but there was always left just a sliver open so you could peer inside. If the director was occupied with writing or on the telephone or in a meeting, you weren’t even allowed to knock on the door. You had to wait in the corridor, with a file under your arm. Sometimes that could be for a long time. You had to just stand there, and be ready to speak immediately you were called inside. That was why the slit was there. So you could be prepared.

At the far end of the corridor was the Taipan’s office. This was where Mr Fong sometimes was called to see Sir John Keswick. It was another very large room, three times the size of the other directors’ offices. Instead of the present dining tables, there had been a big desk in the middle of the room between the two windows facing the Bund. The rest of the room was filled with THINGS, he said. Books, files, cabinets, papers. Tables of papers, all piled high. The room was very dark. Papers and papers. “There’s so much to do,” Sir John would tell him. Meanwhile his secretary sat in a cubby hole between his office and the corridor. “She was always typing,” said Mr Fong. “Never stopped. An English lady. Very nice and efficient.”

On the other side of the corridor today there is a bar, ‘Teddy’s Bar’, in the American style with thick leather armchairs and photos on the wall of the first Roosevelt President in his Rough Riders gear winning the US war with Cuba. Mr Fong told us that in the old days here was the Book Office and beyond it the Shares Office and beyond that the Correspondence Office. It was where the clerks sat writing contracts, letters and bills. “It was the heart of the firm” he said. Close by were Advisers’ offices, and in a very small room right at the back sat J L Koo, the Comprador.

We ended the tour on the eighth floor, which leads onto the roof terrace where there is a restaurant. This part of the building did not exist when Mr Fong was last here. Nor had we been able to stop on the fourth to seventh floors; they were still under renovation. But it did not matter. Mr Fong was beginning to tire. For long moments he leaned over the balcony looking at the towers of Pudong rising on the opposite bank of the Huangpu. They were mud flats when he worked at Jardines. “How it’s changed,“ he said. “How it’s all changed.”

In 1986 Eugene’s father, YC, had tracked down for me 25 fellow former managers, including Mr Fong, and I had organised a Chinese New Year party for them in my flat in the Xinguo Guesthouse. I had found it a very emotionally charged occasion, and so had all the former Jardine staff. “You don’t know what it felt like to be found by the company again,” Mr Fong said, as a slight breeze blew above our heads. “It was like waking up again.”

We exchanged reminiscences. “Do you remember Felix Chen?” he asked, Yes, I remembered Felix Chen. I think it was he who had asked me whether we still imported frozen eggs. Another old man, formerly in charge of communications, had enquired what sort of codes we used in the cable department. “They must be much more complicated than in my time.” It was strange to realise that for these former staff members time had stood still.

Now we were laughing, remembering them all with affection. Somebody mentioned Zhu Tailai, the old timber merchant, who back then was almost as old as Mr Fong is now. That first party he had felt very pleased with himself. After doggedly negotiating with the Government, he had just triumphantly regained his old villa with its beautiful Himalayan pines. But then we fell silent. Mr Zhu had not enjoyed his re-found home for long. The big New Year gatherings had become smaller each year as one face after another became absent from the table. One by one the old managers ailed, then passed away. Mr Fong is the only one left.

Over a coffee in the House of Roosevelt’s Sky Bar he began to speak of the Cultural Revolution. Because of his former association with Jardines he had been taken out of the school where he taught mathematics and English and made to work as a labourer, hauling heavy goods. It was hard, terrible work and Mr Fong was not a strong man. Then he recalled his time working in the Jardine Engineering Corporation. He remembered some of the mechanical techniques he had learned there and applied them to make his hauling work easier and more efficient, and that’s how he got by,

“I was never bitter about Jardines. Or any part of my life,” he said. “I believed one day things would become better. And they did.” He told us that he had taught more than 10,000 students in his lifetime. “That’s something,” he said. “You have to be optimistic. I’ve learned it’s best not to worry, even when things are at their worst. Just relax and hope for the best. That’s how you live to a very old age.”

***

Adam Williams has worked 25 years in China for Jardine Matheson and is presently Group Chief Representative, based in Beijing

For more information on Jardine Matheson & Co’s history see The Thistle and The Jade: A Celebration of 175 Years of Jardine, Matheson & Co.

For more information on Jardine Matheson today see Jardines.com

For more information on the House of Roosevelt see RooseveltChina.com