Exactly one thousand three hundred years ago a mixed army of Arabs and Berbers reached the Straits of Gibraltar. It had taken the forces of Islam less than eighty years from their Prophet’s death to conquer North Africa. Now they were ready to carry their religion into Europe. In 711 they arrived in Spain, easily defeating the Visigothic armies that came against them. By 719 they had subdued the whole peninsula as far as the Pyrenees, driving any remaining Christian opposition into a small enclave of forest and mountain in the north and west. The rest of the country was absorbed into the culture of Islam.

At first it was rape and bloody conquest, as cruel as any invasion of the times. Perhaps the Visigoth peasantry came off lightly compared to what coastal areas of Northern Europe were facing from predatory Danes and Vikings, but few of the conquered Christians steeling themselves to heathen and alien rule as the 8th century turned into the 9th would have imagined that within a hundred years they would contentedly be celebrating their Mass in Arabic, that al-Andaluz as they had learned to call their country would have become a shining beacon of civilisation compared to the rest of Europe still slumbering in the Dark Ages, and that they had a Muslim Caliph to thank for a better and freer lifestyle than almost anywhere else at that time.

Partly this was a by-product of al-Andaluz’s enormous wealth. By the 10th Century, it had become a world power in its own right. With the profits from its trade its emirs had built beautiful mosques and palaces. A centralised state, it had a huge standing army, consisting of mercenaries and slaves from Eastern Europe and North Africa. Its glittering court attracted scholars from all over the known world. When the Emir Abd-ar-Rahman III declared himself Caliph in 912 (in other words asserting supremacy in Islam against the Abbasid Caliphs in Baghdad) there was much to justify his claim to have taken over the Islamic renaissance that had begun a century before in Baghdad. Córdoba, his capital, with a population of 500,000 people, had a huge paper industry, great libraries and pre-eminent schools of medicine, mathematics, philosophy, poetry and music. It was these sciences, many of their texts translated from Latin and Greek, that later formed the basis, when transferred to Northern Europe, of Western knowledge.

Andaluz’s unique strength, however, was the openness of its society, and this attracted even its enemies. Despite the fact that they were at war and dreaded the armed raids of the Caliph and his belligerent Wazir, al-Mansur, every year, affluent young men in the Christian kingdoms of Castile, León and Navarre at the beginning of the 11th Century would in private call themselves Ali or Mohamed. If they were ultra-cool they’d wear Moroccan jelabahs, sip sherbet under orange trees, dress their food with spices, listen to Arab music and take baths. The big dream was one day to visit Córdoba, because Córdoba was New York.

This attractive cosmopolitanism, and the reason why the inhabitants of al-Andaluz – Moors, Christians and Jews – could live in harmony was a result of the deliberate policy of tolerance practised by the caliphs. For sure Arabs ruled and Islam was the State Religion. The laws of the Prophet applied absolutely to every Muslim, and to non-Muslims in the case of dispute – but otherwise Christians and Jews, as long as they paid their taxes, could worship and govern their own communities as they pleased. Different laws co-existed. Nor were positions in the Caliph’s government denied to those of merit from the other communities. One of the chief ministers of Caliph Abd-ar-Rahman III was a Jew, Hasdai Ibn Saprut, and Christians worked as doctors in Muslim hospitals and secretaries in the Chief Qadi’s office (the Qadi was the judge who administered Islamic law). In fact from the public bathhouse to the Caliph’s palace there was nowhere that people of different races and creeds did not mix freely.

It was not always so. Tolerance, as we are discovering in our own post 9-11 times is a fragile plant that all too often nurtures the enemies who seek to destroy it. It is particularly vulnerable to fundamentalism.

One spring day in 851 a Christian monk from a monastery outside Córdoba came into the city and publicly insulted the Prophet. The first reaction from the cultivated Moorish authorities was to reason with him. When he refused to apologise they reluctantly decapitated him for blasphemy as Islamic law demanded. The embarrassed local Christians were glad when it was all over. But the next week another monk came, and after him another. They too were executed. The provocations did not stop. The last to sacrifice himself was the architect of these demonstrations, since canonised as St Eusebius. The result was polarisation of the separate communities, curfews, martial law, a ban on Christians working in public offices, suspicion of the Jews.

Al-Andaluz recovered from that incident, but it was a sign of what was to come. By 1020 the Caliphate, riven with internal dissensions, had collapsed and al-Andaluz split into separate Muslim kingdoms. King Alfonso VI of Castile, the most powerful of the Spanish Christian monarchs, saw his chance and cleverly playing one Arabic state off against each other, in 1085 he conquered the Spanish emirate of Toledo. This was a time of increasing Christian fervour in Europe that in ten years would take a Christian army, sanctioned by the Pope, on crusade to Jerusalem. Alfonso, to assist his territorial gains, was able to profess a similar devotion in order to tap into this force. French monasteries provided him with money. Volunteer crusaders from the north stiffened his armies. The response from the beleaguered Moorish states was to call on help from a Taliban-like Berber tribe in North Africa, the Almoravids. The blue turbaned jihadis crossed over the straits and took the country for themselves. The tolerant spirit of al-Andaluz was crushed in the collision of opposing fundamentalisms. Civilization went into decline for many decades. It re-emerged briefly in the 12th Century. Moorish philosophers like Averroes later influenced learning in the West – but Córdoba was never again as glorious or tolerant as it had been under the Caliphate. And slowly the Christians gained strength and territory.

After 500 years of bitter religious warfare, known as the Reconquista, Ferdinand and Isabella, monarchs of the united crowns of Aragon and Castile, took the last Moorish stronghold of Granada, recovering Spain for Christendom.

In the hundreds of years that followed, Christian Spain did its best to blot out the memory of what it considered to be its shameful Islamic past. The Inquisition expelled the remaining Muslims and later the Jews. The palaces of the Emirs and Caliphs were allowed to crumble to dust, the few remaining mosques were converted to churches. All that remained were a few castles and towers – and a few faint reflections of an eastern civilisation that had once dominated the land: courtyard houses with tiles and colonnades, flamenco, spicy paellas and gardens full of orange trees and palms became part of the national identity, but their Arab origins had been forgotten.

It was not until the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth centuries that Spanish students of architecture and foreign travellers, inspired by the twin fashions for Romanticism and Orientalism, rediscovered this lost Islamic past. When, in the 1830s, writers like Washington Irving, archaeologists like James Cavendish Murphy and painters like John Frederick Lewis or David Roberts brought descriptions and lithographs of the wonders of the Alhambra Palace in Granada to the attention of the Victorian world, the effect was sensational.

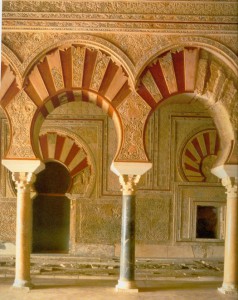

Within a few years write-ups of the Alhambra, the hauntingly beautiful Mesquita mosque in Córdoba, the Arab-style colonnades in the Alcázar in Seville as well as the Torre Del Oro and the Giralda Tower in the same city were in every Baedeker and guide. Trippers in their hundreds came to Spain, braving the rough inns and mule tracks in order to luxuriate their senses on the fabulous arabesques and traceries in the Court of the Myrtles or the Hall of the Ambassadors in the Alhambra, their minds full of images from the Arabian Nights. French, German and English painters obliged the fashion and soon there was a whole school of artists conjuring images of slave girls in harems, Berber guards by imposing gateways and executioners with great scimitars beheading their victims on palace steps.

Times have moved on since then. Modern scholarship has dispelled most of the Arabian Nights fantasies of cruel sultans and beautiful odalisques. Why al-Andaluz fascinates today is because of its parallels to our own times. Our societies too have reached an unparalleled advance of sciences, art, civil society and personal freedoms, but in the wake of the war on terror and the recent collapse of some of our economies, the tolerance which has been the wellspring of our civilisation seems threatened.

For the Spaniards the Moorish period is no longer a time of national shame. On the contrary, in a country that in the last century suffered the horrors of civil war and a 30-year repressive dictatorship, recognising its Moorish past for what it was has been a liberating as well as enriching part of its national renewal. And much pride, mixed with sorrow. It is no coincidence that following the national tragedy in 2004 when trains in Madrid were attacked by al-Qaeda with much loss of life, the Spanish people, uniquely in the Western world, did not fall in behind America on its crusade against terror; they voted in a new Government that was against sending troops to Iraq. Perhaps after a millennium of intolerance – from the Spanish Inquisition to Franco – the Spanish understand divisiveness better than any other nation.

For the tourist, international or domestic, visiting the Alhambra or the Mesquita for the first or the nth time, there is poignancy as well as a beauty.

Click here to order ‘The Book of the Alchemist’ from Amazon.co.uk