I was reading a new book from the Earnshaw Press today. It’s called ‘China Rhymes’ and is a collection of Old China Coast poetry, written in the 1930s by the “poet laureate” of the Treaty Ports, Shamus A’ Rabbit. It has recently joined the growing collection of books published by the Shanghai-based entrepreneur and man-of-letters, Graham Earnshaw, who a few years ago , set himself the magnificent challenge of rescuing for posterity all the early Twentieth Century out of print China Classics ( see the website Tales of Old China).

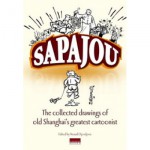

Rabbit’s light hearted poems and ballads are mainly the sort of occasional pieces that first saw light of day in the columns of newspapers like the South China Morning Post, Japan Times and China Mail and conjure a charming and irreverent picture of treaty port life, beautifully illustrated by the great Russian cartoonist, Sapajou (Volume I of whose own Collected Works has also just been published by Earnshaw Books. Get it! It’s beautiful! And a historical treasure).

‘China Rhymes’ made me recall various poems my mother remembered from her childhood in the 1930s in Tientsin (China’s northern treaty port) and which she repeated to me when I was little. But there was a difference. Most of the poems my mother taught me as a child were not in standard English, as Rabbit’s are, but in what was then called Pidgin. This was an argot of mixed Chinese and English adopted primarily for trade and later extended into every aspect of daily commerce. A language in itself, it was used all along the China Coast from the early Nineteenth Century until the mid Twentieth.

To talk – or even repeat – Pidgin is now considered to be somehow politically incorrect. as if it was another crime of Imperial Empire Builders to make Chinese coolies use a comic and demeaning version of English as part of the great National shame game (I was criticised for having a Chinese cook speak it to his British employer in one of my novels set in the 1920s) but nobody would have felt the slightest bit embarrassed or demeaned by it at the time. In fact, most Chinese and British talked to each other in the 1920s and 1930s in nothing else. Without the range of language schools we have today, it was very rare that Chinese or foreigners knew enough of each other’s language to converse fluently except for a small, educated minority – but trade had to go on, and Pidgin could be picked up by anybody. It was actually a very flexible language, and not unique either – there are several other originally ‘Pidgin’ type languages that have been adopted as main line ones – Swahili or Malay, for example, and the official language of New Guinea where the main newspaper was (and still is for all I know) called the New Guinea Talk Talk. But in its day the China Coast version defined Pidgin. It was mainly a transliteration of Chinese grammar using garbled versions of English words. Some of the phrases, “catchee” for “to have” or “to own”, “belong” for “pertaining to” and “makee” for “do” or “cause”, “top side” for “up” and “bottom side” for “down” were still in use when I was a boy in Hong Kong. In fact I have an abiding memory of a family outing to Macau. We alighted from the ferry and found a rickshaw puller.. We wanted him to take us to the beautiful Protestant Cemetery, which, as afficianados of colonial cemeteries and those with a passion for the melancholy of history will know, is a gem of its kind, its gravestones carved with the names of famous missionaries, diplomats and soldiers, alongside heart wrenching crosses and angels (so familiar in the tropics) that mark the graves of tiny children. But could we make ourselves understood to the rickshaw man? We tried English. We made an attempt at Cantonese, but the rickshaw puller stared us uncomprehendingly. Finally my mother lost patience: “Dead man long time down bottom-side,” she snapped, and we were pulled to our destination like a shot.

It was with enormous pleasure that I found in a second hand book shop a small yellow volume of verse, an 1887 version printed by Trübner & Co, Ludgate Hill, London , of the popular ‘Pidgin English Sing Song, or Songs and Stories in the China-English Dialect”. First published in 1876, it was the work of an American humorist and folklorist, Charles Godfrey Leland,, who was born in 1824. I’d never heard of him but I subsequently discovered that he’d lived a colourful life, taking part, among other things, in the 1848 revolution in France and the American Civil War. He is credited as having created the industrial art movement in the USA and wrote occult books. He was also, it appears, a sort of Nineteenth Century Gavin Menzies: one of his most successful books was called “ Fu-sang; or The Discovery of America by Chinese Buddhist Priests in the Fifth Century.” (for those interested there’s a biography of him that can be bought on Amazon Charles G. Leland: The Man & the Myth). But for me, his importance lies as a talented balladeer and promoter of Pidgin.

While many of his poems are comic or nonsense rhymes:

Slang-Whang, he Chinaman

Catchee school in Yangtsze-Kiang,

He larn pidgin sit top-side gloun’

An’ leedee lesson upside down,

With Yatsh-ery – putsh-ery, snap an’ sneeze,

So fash’ he chilo leed ChineseSlang-Whang, when makee noise,

Wit’h he pigtail floggee állo boys,

Allo this pidgin much tim go,

What tim good olo Empelor Slo.

An’ no more now in Yangtsze-Kiang

Hab got one teacher good like Slang.

some are lyrical, like this ballad about a Chinese princess married off to the ‘colo-lan’ ‘ (cold lands) of Tartary:

Belongey China Empelor

My makee one piecee sing:

He catchee one cow-chilo

She waifo Tartar king,

Hab lib in colo-lan’,

Hab stop where ice belong,

What-tim much solly in-i-sy

She makee t’his sing-song:

“He wind he wailo ‘way,

He wind he wailo ‘long,

An’ bleeze blow ovely almon’tlee,

And cally a birdo song.“Too muchee li to China-side

T’hat-place he tlee glow high,

My fáta blongey palace,

All golo in-i-sy,

My wantchee look-see máta,

He máta wantchee kai,

My tinkey Mongol fashiono

No plopa fashion my.

Ai! Wind he wailo ‘way

Ai! Wind he wailo long,

An’ bleeze blow ovely almon’tlee,

And cally a birdo song.“He birdo wailo Pay-chin,

Chop-chop he makee fly;

That máta hear he sing-song,

How muchee dáta cly,

‘How tartar-side he colo’

How muchee nicee warm,

One dáta-chilo catchee

In-i-sy he máta arm.

Ai! Wind he wailo ‘way

Ai! Wind he wailo long,

An’ bleeze blow ovely almon’tlee,

And cally a birdo song.“He go top-sidee cow,

T’hat fashion tartar-side,

T’hat no be plopa fashion

For Pili-kai to lide.

Suppose he lib homo,

So-fashion he look-see,

He lide fo’ piece horsey

In coachee galantee.

Ai! Wind he wailo ‘way

Ai! Wind he wailo long,

An’ bleeze blow ovely almon’tlee,

And cally a birdo song.”He máta talkee Pili :

He Pili open han’,

He talkee, “No good fashion

Hab got in Tartar-lan’.

Must make one China town,

Must makee for he kai;

Must makee tartar-sidee,

An’ he no makee cly.”

Ai! Wind he wailo ‘way

Ai! Wind he wailo long,

An’ bleeze blow ovely almon’tlee,

And cally a birdo song.He sendee muchee coolie,

He sendee smartee man,

He makee China city

In-i-sy t’hat Tartar lan’.

He kai catch plopa palace

An’ coachey galantee,

No more hab makee cly cly.

My sing-song finishee.

Ai! Wind he wailo ‘way

Ai! Wind he wailo long,

An’ bleeze blow ovely almon’tlee,

And cally a birdo song.

Glossary

- Cow-chilo – daughter

- Colo lan’ – cold country ie Tartary

- Solly – in grief

- In-i-sy – inside

- Wailo – go

- Cally – carry

- Li – a Chinese mile

- Fáta – father

- Golo – gold

- Máta – mother

- Kai – daughter

- Plopa – proper

- Pay-chin – Pekin

- Chop-chop – quickly

- Pili-kai – Emperor’s daughter

- Homo – home

- So fashion he look-see – She would appear thus

- Fo’ – four

- Galantee – grand

- He máta talkee Pili – The mother addressed the Emperor

- Tartar-sidee – in Tartary

I suspect that Leland considered that he was writing seriously in a respectable dialect. (In his introduction he describes the language in philological terms and attaches a useful glossary at the end). ‘Pidgin English Sing Song’ was certainly a labour of love, and, politically incorrect though it may be for the sourpusses, reading him today is a delight.

Since it’s still the Christmas Season (still a few days off Twelfth Night) I’ll add one more of his poems, one which in the 1880s must, I am sure, have found itself scribbled on greetings cards all along the China Coast, because it is a reworking (in Pidgin) of something very traditional and English:

Littee Jack Horner

Makee sit inside corner

Chow-chow he Clistmas pie;

He put inside t’um

Hab catchee one plum

“Hai yah! What one good chile my!

Buy Adam Williams’ China trilogy – The Palace of Heavenly Pleasure, The Emperor’s Bones and The Dragon’s Tail – from Amazon.

Wotcher Adam!

My favourite pidgin phrase is from Papua New Guinea where a helicopter was “mix massa belong Jesus Chriss”.

Apparently the missionaries used to travel by chopper…

Love the website by the way.