Definition of ‘Bradshaw Art’ in Wikipedia:

“Bradshaw rock paintings, Bradshaw rock art, Bradshaw figures or The Bradshaws, are terms used to describe one of the two major regional traditions of rock art found in the north-west Kimberley region of Western Australia. The identity of who painted these figures and the age of the art are contended within archaeology and amongst Australian rock art researchers. These aspects have been debated since the works were first discovered and recorded by pastoralist Joseph Bradshaw in 1891, after whom they were named. As the Kimberley is home to various Aboriginal language groups, the rock art is referred to and known by many different Aboriginal names, the most common of which are Gwion Gwion or Giro Giro. The art consists primarily of human figures ornamented with accessories such as bags, tassels and headdresses.”

Description of Bradshaw Art in ‘Lost World of the Kimberley’ by Ian Wilson:

“(Bradshaw rock) paintings exist in literally tens of thousands across an area almost the size of Spain. And an awareness and even partial understanding of them is arguably fundamental to our understanding of the whole history of humankind in its Ice Age infancy. Unless there is some fatal flaw to the dating of these paintings, back at a time when most of Europe lay deep beneath ice sheets a people in Australia were creating elaborate garments for themselves, building ocean-going boats, cultivating root crops and enjoying a rich ceremonial life. Not least, they were creating figurative paintings of verve and talent that surpasses all of the world’s rock art, and would not be seen again until the rise of the ancient Egyptian and Near eastern civilizations.”

From ‘Bradshaw Rock Art of the Kimberley: A Photographic Insight’ by Lee Scott Virtue & Dean Goodgame:

“The Bradshaw rock art images are intriguing and unlike most other rock art images found in the Kimberley, they show a progressive decline in artistic technique and ability. This provides an interesting mystery yet to be solved and raises many questions. Are the first Classic Realistic images the result of an early migration of a different culture? Did this ‘Bradshaw’ culture then intermarry with the local indigenous groups or, did they merely pass on their knowledge to provide a visual glimpse of their own cultural identity? Politically correct ‘speak’ is currently interfering with research so it is difficult to see the real results of current ‘peer reviewed’ papers coming from the current Kimberley archaeological programs.”

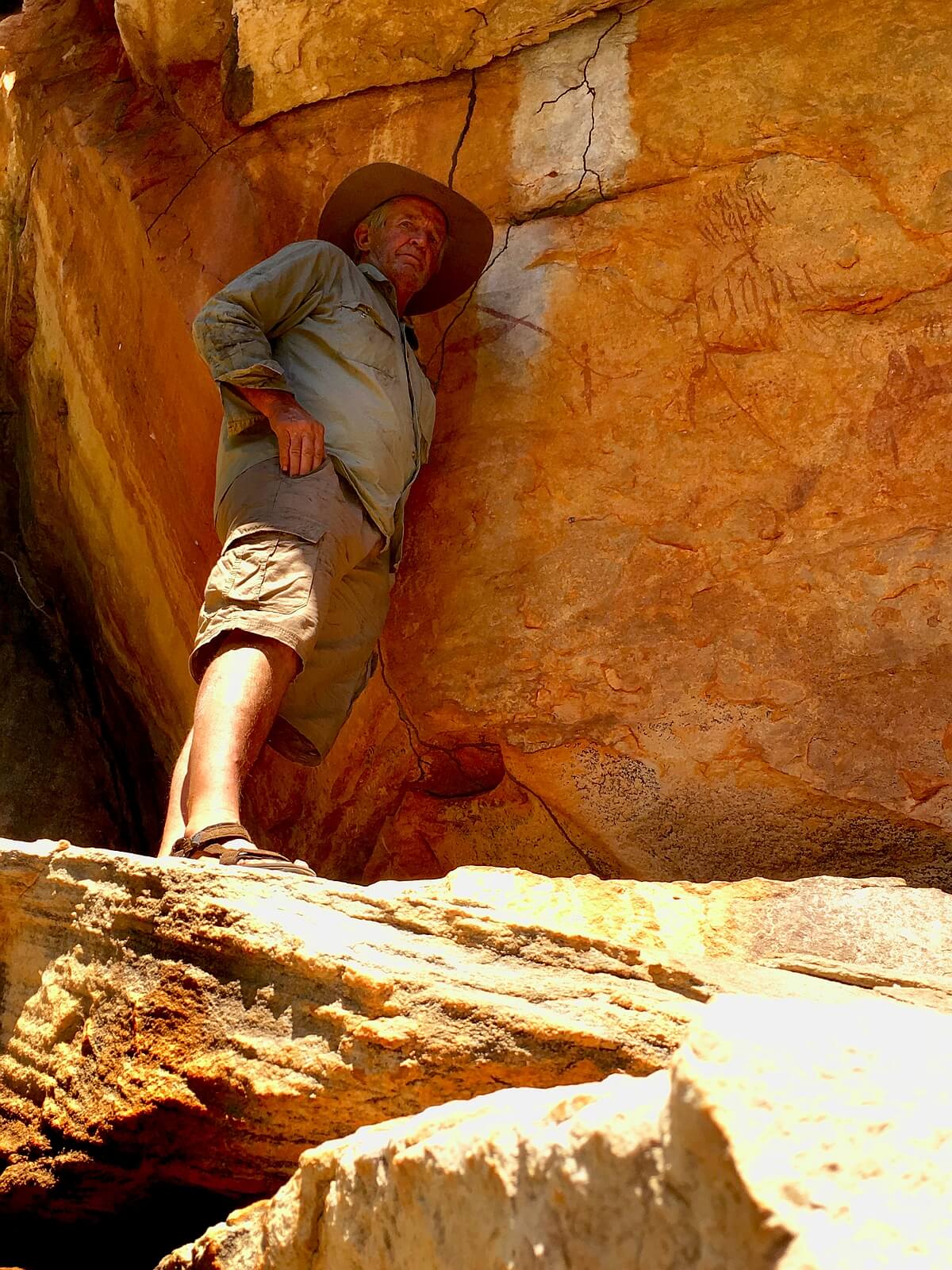

We gathered in the small town of Kununurra, where my companions on this trip, Berwyn Lewis and Daniel Rowland, the one a famous journalist, the other a semi-retired lawyer and former CEO of the Australian Film Commission, and I had the good fortune to be briefed by two of Australia’s few experts on the Bradshaw rock art, Lee Scott Virtue and her business partner Juju Wilson. We also met our matchless guide, Scotty Connell. It would take us three days and more than 500 km of unpaved roads to get us to our destination at Mitchell Falls, location of some of the most spectacular and accessible of Bradshaw/Gwion Gwion art. On the first evening, camping at the Drysdale River Campsite, we picked up Brownie, a veteran not to say legend of the Kimberley. An iconic guide, few had his knowledge of the area, particularly the Mitchell Plateau where he had been a Park Ranger for a decade, nor his understanding of Aboriginal lore and history, including the location of every sacred site in an area of several hundred square miles. Having with us Scotty and his bush knowledge and Brownie with his encyclopedic sense of history and philosophy made our rough camping expedition five star, and our visits to the rock art sites an intellectual voyage of discovery.

The accompanying film of photographs will show where we went and what we saw.

As far as my own parochial wish was concerned, to discover a cathedral at the end of an ersatz pilgrimage, I was as awed and humbled as I hoped to be. We had a taste of what was to come at Munurru, on the edge of the Mitchell Escarpment. As on the Jatbula Trail each site had its own aura of age and sanctity. Pavilions of rocks surrounded rings of flat ground that could have been used for the ceremonies and dances, depicted in the paintings. There were bones nestled in some of the crevices. Almost every flat surface was painted, mainly with Aboriginal drawings in the Wandjina style, which is usually dated to be around 3000 years old, but peeping out behind the huge images of round headed, round eyed spaceman-like ancestors and huge white child-stealing monsters, emerging through millennia of fading paint that had covered them, reappearing in strong red or brown ochre, as light and delicate as the day they were painted, could be perceived smaller, older figures – lithe, tasseled, human, with flowing hair or tall hats, their limbs elegantly and anatomically correct, full of life and movement.

We came upon one flat surface, a fresco-like panel on a lone standing rock, where four large dancing figures greeted us, as fresh as if they were hanging in a modern gallery. Brownie said this was a “window to the past”. He took us round the corner to one of the circles and asked us to sit in silence. “For a minute,” he suggested. We were as immobile as statues for at least ten minutes, when a startled tourist startled us by saying, “Is it all right to pass by?” We shivered back to the present. I remembered a birdcall. That had been the only sound I had heard above the slight sigh of the wind that had wafted us into the past during our trance. As at the cascade on the Jatbula I had felt myself one with the surroundings.

Bradshaw/Gwion art at Upper Mitchell Falls

That was our introduction to the Bradshaws. What awaited us above and below the Mitchell Falls was even more amazing. There I found my cathedral. Actually, there are two of them. They can be seen in the film, one a whole wall of Bradshaws from the older ‘Complex’ period, in a scene so full of movement and life that it might have presaged a Renaissance tableau of the Muses; then, below the waterfall, further away towards our camp, a cave, with outside a tumbling water fall, and below it a lake – another veritable cathedral, with Bradshaws covering its stone slab cloisters. They were drawn in the cruder style of the later, inferior “Straight Figure” period, but they were still impressive for their age. Maybe 20,000 year old, there was nothing in Europe to match them at the time, or for thousands of years to come and they included possibly the first battle scene ever painted, but next to them were drawings even more impressive: black stencils of yams and snakes, turtles and kangaroos, delineated as carefully and correctly as a sketch by Banks or Linnaeus, and these were conceivably 50,000 years old, preceding even the Bradshaws. It was as if we had come across a carving of an Earth Mother in a grotto of Greek statues. I stumbled away, almost replete with wonders.

It took us two days to return to civilization – Scotty wanted to give us a day at the prestigious El Questro resort, close to the magnificent Cockburn Range of hills, all the slopes and canyons of which he had explored, outside the tourist season, in the baking summer when the bush was his own to wander in. El Questro is frequented by Hollywood stars, who rent the $4,500 a night bungalows for a taste of wilderness, but there was a campsite for us cheaper travellers, and we were able to take a boat ride through the ancient Chamberlain Gorge. We found ourselves going even further back in time. It had already been humbling to be taken back 30,000 years more or less by the Bradshaws. Here, clearly visible, was a geological past that went back millions of years. On the cliffs on either side, the discolorations showed us strata of red and black rock, that had formed their present shape in an earthquake that had taken place 1.6 billion years before the Bradshaws were even heard of, or humans for that matter.

By this time I was feeling very humble indeed.

Berwyn, Daniel and I had been enormously lucky. With the benefit of such experienced guides, we had been served up wonders. However, no traveller in this region can leave unaware of the snake of politics that has wormed its way into this paradise in recent years, very much centred on the Bradshaw/Gwion sites and their ‘ownership’. Access to many sites are restricted or discouraged. There are arguments about the origins, the dates and even the generic name. They have been plucked from the realm of history, art and archaeology and embroiled in the national debate over Aboriginal rights. The danger is that, neglected, this delicate art itself may become the victim, and a heritage of history belonging to every Australian will be compromised.

I am no Australian, but I also feel a passionate kinship with these paintings. It is quite possible that they are remains of one of the first, or even the first advanced civilization on the planet. Depictions of high-prowed, sea-worthy boats suggest a contact with Indonesia when it was a continent. There are tantalizing archaeological indications that there existed a thriving culture before floods caused by the melting of the North American ice sheets 18,000 to 8000 years ago reduced the landmass to islands. Survivors of that inundation might well have travelled west as well as east, possibly initiating the civilizations that grew up in Egypt and even Europe – see for example “Eden in the East – The Drowned Continent of Southeast Asia” by Stephen Oppenheimer or “Magicians of the Gods” by Graham Hancock.

Whoever painted them, these ethereal and mysterious paintings need protecting. On our journey we saw signs of bush fires perilously close to some of the sites. There do need to be controls – but there also needs to be a more general knowledge of their existence, because this unique, not to mention beautiful, art form may have a major part to play in understanding our origins not in the context of a particular race but of mankind as a whole. If the Government of Australia perhaps in association with the UNESCO World Heritage program can achieve this, it would be a benefit to our greater understanding of who we are and where human civilization began.

Dear Brian, My apologies for not spotting this post of yours earlier. The more I hear and see the more fascinating I find these mysteries. It has become a political matter with the Native Australians making claim to all archaeological claims, but there are enough differences in style between later art and older art which raise questions of whether there might have been another race living in the Kimberleys at one time, perhaps linked to the culture in Indonesia which before the floods in 8000 BC odd was a sub-continent the size of India. And from what I read in magazines like Nexus, it seems there are much older skeletal remains in Australia – many of them supposed giants and some with strange shaped skulls. Maybe Nexus magazine might be a good start to hear about these stories – I remember one article which described how in the 19th century in America there were huge discoveries of giant skeletons i, similar to some that have been found in Australia . I have no knowledge of these matters, I’m only a traveller with a fascination like you, and sometimes I wonder if I should take some of this talk with a pinch of salt – but that said every year brings new finds that challenge orthodoxy and push the age of mankind and not to mention some form of advanced civilization further and further back in time, Adam

I worked in mining exploration in Western Australia in 1960-70 and in Pilbara. I met an old white prospector looking for Tantalite in 1971 near Marble Bar who was brought up in the Kimberlies and was initiated into the tribal law and was the first person to drive a vehicle to the north coast of the Kimberlies. He had a photgraphic knowledge of the Kimberlies and had assisted Japanese mining company people with early helicopter explorations. He also said Japanese sign language was very similar to the aboriginal sign language he had learnt. He also supported a German lady anthropologist to view with tribal consent sacred objects and sites to which she was intermittently blindfolded. However of much interest when he was tracking dingoes he crawled into an opening that opened to a large cave. In it he described Von Danikan like wall paintings and the open area was big enough to drive a vehicle around. In part of the cave was a raised platform and laid out were many very tall skeletons in straight posture unlike aboriginal fetal posture burial. They had large skulls that were thin like egg shells he said, and poked his finger into one, all was most unusual. In the mid nineties I met a local driller ( Brian ??) in Halls Creek who knew of this place too and said how did I know as it is a big secret. He knew the Kimberlies extensively too having drilled most places in 20 + years of his business there at that time. What are they, Bradshaw skeletons?